When aligning all texts on a page/spread, should every element be aligned according to some sort of structured grid? (pg. 118-199)

Working on the book cover design drafts made me realize (via Professor Dell’Orto’s correction marks) how important it is just to move the title a few points, just to align with the texts on the side flaps. This has gotten me to think, when designing a layout, does every single element have to be aligned according to some sort of structured grid?

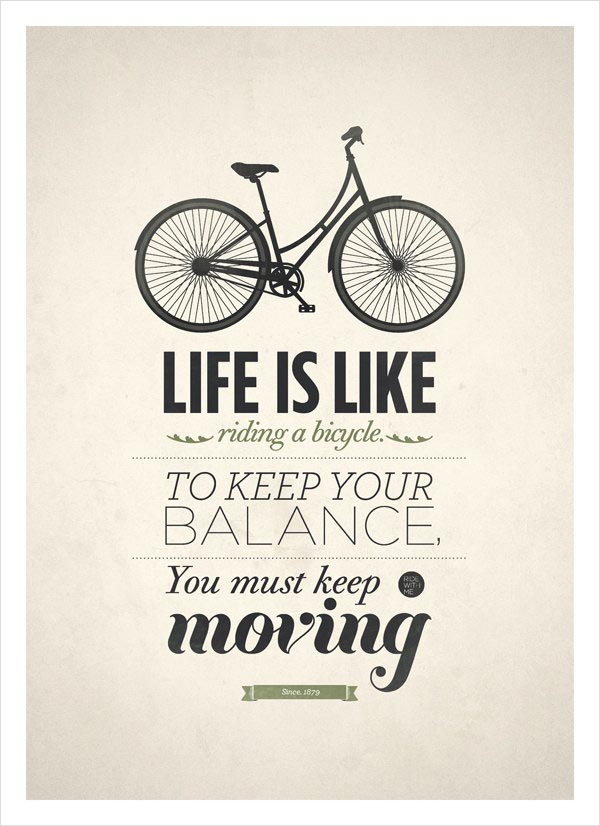

I found this fantastic tutorial on typophile, with instructions on how to create a baseline grid. In it, even each line of the different columns (of different sizes and weight) still aligned to each other– something I haven’t really thought about before:

In other exercises, I don’t think I’ve ever really aligned blocks of texts (of different sizes/weight) because I didn’t think it really mattered; plus, with the different sizes, I would think it’s tricky to align the different elements perfectly anyway!

As you can see in the image above, everything is aligned perfectly on a baseline grid. Simply by aligning everything, the whole layout has so much structure and legibility. It also looks effortlessly clean!

Although this topic seeps into the “GRID” section, there is a close relationship between grids and alignment. If you have a grid envisioned for your layout, you will have elements aligning nicely on the page.