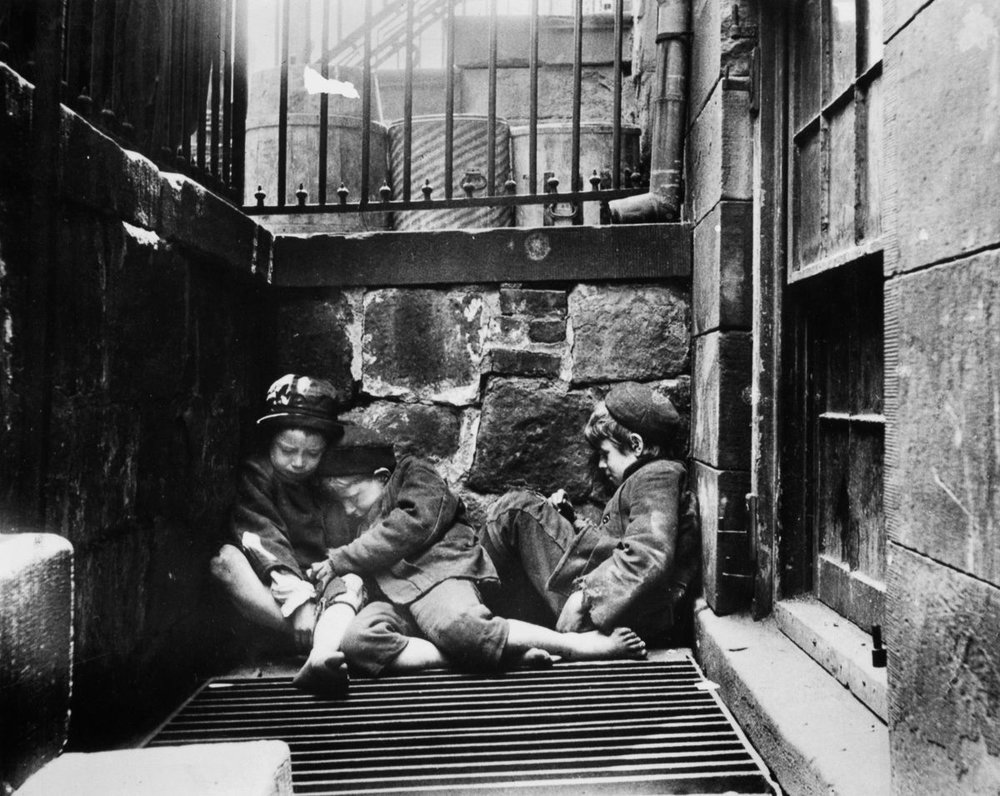

During the late nineteenth century, New York City’s densely populated, poor neighborhoods were overloaded with atrocious tenement housing. Among the poorest neighborhoods was New York’s Lower East side, once referred to as “Poverty Hollow.” Sanitary and living conditions made it a breeding ground for premature death and illness. Often considered responsible for their own misfortune, the poor were blamed for their dreadful living circumstances and frequently went without aide. Sympathetic to their needs, a young Lilian Wald, devoted her life to the care and well-being of the city’s poorest. In 1893, she created the Nurse’s Settlement, renamed the Henry Street Settlement. Over the next one hundred twenty six years, the settlement contributed to the health and welfare of thousands of New Yorkers.

Baring witness to the extreme poverty, Nurse Lillian Wald moved into a tenement on the Lower East Side, where she created and housed the Nurse’s Settlement for the first two years. Her connections and diligent advocacy for philanthropic support resulted in the donation of a townhouse at 265 Henry Street, by banker Jacob H. Schiff. Shortly after the completion in 1895, Wald moved into the townhouse and it became the center of the settlement’s activities. As the scope of work for the settlement house grew, the property grew to incorporate 263, 267, 299, 301, and 303 Henry Street and multiple satellite offices located throughout the city. Wald’s dedication to the Lower East Side and humanitarian work was showcased throughout the Henry Street Settlement and the community she served.

As a professional nurse, Wald labored endlessly to provide vital aide to the community. Her fundamental visons on public health service established the Henry Street Settlement as a national example in care for the poor. As part of her legacy she coined the term public health nursing, which sought after treatment of social and health problems amongst the patients served. Her accomplishments impacted nursing, the Lower East Side, and New York City. Perhaps her most important contribution was the establishment of the Visiting Nurse Service. Prior to its separation from the Henry Street Settlement, the Visiting Nurse Service carried out the greatest volume of health work amongst any established settlement. Each year the visiting nurses cared for thousands of patients, made hundreds of thousands of home visits, educated parents at prenatal centers and preschools, and provided care for nursing mothers. The Visiting Nurse Service worked meticulously through the generations to meet the needs of a changing city. They worked closely with the immigrant and black communities which were amongst the poorest and had the least access to health services. With dangerous outbreaks of polio, influenza, and diphtheria in the city their work became vital to the health of the city. Their work did not only include treating those who become ill, they also educated the poor to treat and prevent illness within their families. The educational aspect was a major focal point in Wald’s vision for the poor.

In her creation of the Henry Street Settlement, Lillian Wald strove to defend the moral worth of the poor by offering educational and social opportunities. She moved into Settlement as a neighbor and companion to those who needed her help. The Henry Street Settlement became a beacon for social change. The staff involved itself in issues concerning child labor laws, public housing, special education, and public education. Believing that recreation was crucial to childhood development, Wald turned the Settlement’s backyard into one of the first public playgrounds. Many children were sent outside to escape the dangers of overcrowded tenements and left to play in the streets. The park became a safe haven for the children to play and families to nurture childhood recreation. The Settlement house also put the first school nurse on payroll which prompted the Board of Education to employ nurses in public schools. Many students missed school or were sent home due to minor, but often contagious, ailments such as lice; yet others went undetected and continued to spread illness to healthy students. Wald’s thorough research and trustworthy relationship with the Board of Health helped to advocate for medical inspections of public schools, leading to medical care for more students and an increase in the attendance of poor students. The Henry Street House would continue to meet the social needs of the New York’s poorest inhabitants, changing its focus with the changing times.

Today the Henry Street Settlement House remains an essential life line to the city’s poor. In 1976, 263, 265, and 267 collectively became a national historic landmark. Lillian Wald’s philosophy of nurture and care for the poor has lamented for generations after she left the staff at the Settlement house. As the eras have changed, the settlement adjusts its focus towards important community issues, currently they are assisting victims of domestic violence and educating community members on the importance of voting. With one hundred twenty-six years of service, the Henry Street Settlement House has greatly impacted the overall health of the city and has afforded opportunities to millions of New Yorkers.

Today the Henry Street Settlement House remains an essential life line to the city’s poor. In 1976, 263, 265, and 267 collectively became a national historic landmark. Lillian Wald’s philosophy of nurture and care for the poor has lamented for generations after she left the staff at the Settlement house. As the eras have changed, the settlement adjusts its focus towards important community issues, currently they are assisting victims of domestic violence and educating community members on the importance of voting. With one hundred twenty-six years of service, the Henry Street Settlement House has greatly impacted the overall health of the city and has afforded opportunities to millions of New Yorkers.

Resources

Fee, Elizabeth, and Liping Bu. “The Origins of Public Health Nursing: the Henry Street Visiting Nurse Service.” American Journal of Public Health, American Public Health Association, July 2010, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2882394/.

Henry Street Settlement, www.henrystreet.org/about/our-history/exhibit-the-house-on-henry-street/.

Kraus, Harry P. The Settlement House Movement in New York City, 1886-1914. Arno Press, 1980.

“Menu.” Lillian Wald Public Health Progressive, www.lillianwald.com/?page_id=457.

“VNSNY History | Home Care Agency | Home Health Care.” Visiting Nurse Service of New York, www.vnsny.org/who-we-are/about-us/history/.

The hospital is just a short F train ride away, but what stands there today is a building that is hard to imagine as NYC history. Roosevelt Island is wedged just between Queens and the Upper East Side, now largely a residential area, but just a few minutes south is the decaying gothic ruin. The stone building has collapsed in some areas, engulfed by ivy, and only a shell of its former self. The entirety of the interior has given way and both wire and iron fences now line the foundations to keep out the curious. Over the years, the smallpox hospital has attracted a surprisingly steady influx of onlookers on its own but largely due to the theory that its ruins are home to the paranormal.

The hospital is just a short F train ride away, but what stands there today is a building that is hard to imagine as NYC history. Roosevelt Island is wedged just between Queens and the Upper East Side, now largely a residential area, but just a few minutes south is the decaying gothic ruin. The stone building has collapsed in some areas, engulfed by ivy, and only a shell of its former self. The entirety of the interior has given way and both wire and iron fences now line the foundations to keep out the curious. Over the years, the smallpox hospital has attracted a surprisingly steady influx of onlookers on its own but largely due to the theory that its ruins are home to the paranormal.  The hospital, after twenty years of service, was eventually converted into a nursing school complete with quarters after the smallpox epidemic had subsided. Ever since the mid 20th century, the smallpox hospital has become dormant and only continues to decay. Many NYC historical conservation groups seek to preserve the location but its history and fate are looking grim, muc

The hospital, after twenty years of service, was eventually converted into a nursing school complete with quarters after the smallpox epidemic had subsided. Ever since the mid 20th century, the smallpox hospital has become dormant and only continues to decay. Many NYC historical conservation groups seek to preserve the location but its history and fate are looking grim, muc

(Remnants of the 42nd St. Reservoir that can still be seen in the New York Public Library. Photos courtesy of Dylan O’Connor)

(Remnants of the 42nd St. Reservoir that can still be seen in the New York Public Library. Photos courtesy of Dylan O’Connor)

he Weill Cornell Medical College is a medical school part of Cornell University. It is located on 1300 York Avenue and overlooks the East River. The school was founded in 1898 and was one of first American medical colleges to offer a four-year program in natural science in addition to an existing two-year medical program. The school was founded through an endowment by Colonel Oliver H. Payne, the son of a wealthy Standard Oil businessman. Payne became interested in medicine through his college friends Dr. Lewis A. Stimson and Dr. Henry P. Loomis. At the time, they worked for the University Medical College which was a part of New York University. Colonel Payne was so interested and supportive of his friend Dr. Loomis’ research, that he created a laboratory for him in his name.

he Weill Cornell Medical College is a medical school part of Cornell University. It is located on 1300 York Avenue and overlooks the East River. The school was founded in 1898 and was one of first American medical colleges to offer a four-year program in natural science in addition to an existing two-year medical program. The school was founded through an endowment by Colonel Oliver H. Payne, the son of a wealthy Standard Oil businessman. Payne became interested in medicine through his college friends Dr. Lewis A. Stimson and Dr. Henry P. Loomis. At the time, they worked for the University Medical College which was a part of New York University. Colonel Payne was so interested and supportive of his friend Dr. Loomis’ research, that he created a laboratory for him in his name.