In 1882, Congress passed and the president signed an order barring all Chinese laborers from entering the United States for ten years and enshrining previous court decisions denying Chinese aliens the right to naturalize. In 1892, Congress extended the ban for another ten years and in 1902 made it permanent. The 1882 act was the first law to bar a particular nationality from immigrating; by 1924, only Filipinos, colonial subjects of the United States, could migrate to this country from Asia.

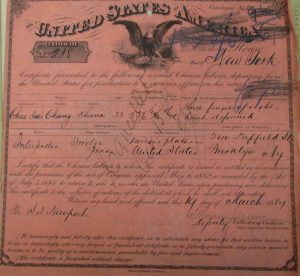

The 1892 legislation also required Chinese laborers already in the United States to “apply to the collector of internal revenue of their respective districts, within one year after the passage of this act, for a certificate of residence.” Although Chinese organizations, especially the Six Companies, organized massive resistance to registration, their resistance failed. Eventually, the vast majority of laborers registered–the first mass registration of an ethnic or national group in US history.

In 1888, Congress also passed the Scott Act, which made it “unlawful for any Chinese laborer who shall at any time heretofore have been, or who may now or hereafter be, a resident within the United States, and who shall have departed, or shall depart, therefrom, and shall not have returned before the passage of this act, to return to, or remain in, the United States.” Chinese legal residents caught abroad when Congress passed the act were never allowed to return; the US had unilaterally cancelled their return certificates, and 20,000 were permanently shut out.

Today, historians consider the Chinese Exclusion Act and the legislation related to it part of a shameful period in American history when racism guided policy. The late 19th and early 20th centuries contain many examples of this, such as the dawn of the Jim Crow era in the South, the disfranchisement of black voters there, and the terrible mistreatment of Native Americans throughout the country.

In New York City, Chinese Americans suffered as well. Those born in the US but illiterate in English grappled with literacy laws that disfranchised them. Immigration agents raided Chinese American homes and businesses, seeking seamen who had jumped ship, people who had unlawfully entered the US through Canada and Mexico, and others who could not prove their right to be in the United States. This kind of repressive enforcement was not only racially targeted, but it also encouraged vindictive residents of all backgrounds to anonymously report to immigration officials any Chinese they did not like. A tipster turned in William Chung, then living in a Bronx laundry, in 1915. Chung had actually been born in the United States but did not have any papers with him to prove it; the Immigration Service only released him several months later, after he established his citizenship by finding documents that positively identified him. The episode was a frightening reminder to Chung and his peers that as Chinese Americans, they could always face anonymous, racially-based harassment.

At times, the political climate also encouraged immigration enforcement officials to abuse their power. In the 1950s, politicians and officials within the State Department used fears of communist China to encourage harsher immigration enforcement in the United States. During a nationwide crackdown on alleged Chinese immigration fraud in 1956, FBI agents stopped ethnic Chinese in Chinatowns across the country and demanded proof of their right to be in the United States. In New York, the crackdown empowered right-wing community leaders with ties to the Nationalist regime on Taiwan and discouraged left-wing and moderate political activism for many years. In other words, immigration agents essentially served as enforcers for a repressive political group.

Sadly, the current administration seems bent on a return to this era. President Trump’s hastily issued executive order barring refugees, migrants, and even green card holders and dual citizens from seven Muslim majority countries recalls the worst episodes of racism in our immigration history. Courts around the country have now stopped its enforcement, but the president seems bent on finding other ways to push American immigration law and practice back to its worst period.