Several of the more recent posts on this site come from research I did for my third book, American Exodus: Second-Generation Chinese Americans in China, 1901-1949. The book is now out, and I’ll be doing a few talks about it in the months to come.

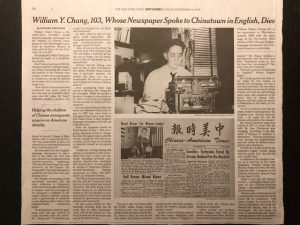

Farewell to a Pioneer

The Hawaiian-born New York journalist William Yukon Chang died on September 4, 2019, and his obituary appeared in the New York Times yesterday morning. (The online version is here. The World Journal also published its own obituary here.)

I was fortunate to meet Bill for the first time about seven years ago, when I had dim sum with him, his daughter Dallas, and my friend and fellow historian Ellen Wu at Nom Wah in Manhattan’s Chinatown. That meal inspired my 2013 blog post about the first office of Bill’s Chinese-American Times, the newspaper he founded in his family’s home in Forest Hills. The Changs, and the CAT, later moved to Manhattan’s Chinatown.

Over the past few years, I not only got to know Bill better but also had the chance to help Dallas organize his papers for donation to Columbia University. Bill lived an amazing life, and I’m grateful to have known him for some of that time.

#31: Defending the Free Press

Completed in 1960, the rippling, modernist Chatham Green cooperative apartment building (165-215 Park Row) dominates the intersection of Park Row and Worth and St. James Streets to the southeast of the old core of Chinatown. Between 1928 and the mid-1950s, however, the buildings on this stretch of Park Row contained a mix of businesses, including a number of printing and newspaper offices similar to those found up the street near City Hall Park. Located next to the Venice Theater, the building at 211 Park Row housed a print shop and the office of the Shangbao (紐約商報)–the Chinese Journal of Commerce, as it was known in English–until 1944, and then the China Post (大華旬刊, literally the Greater China Semi-Monthly) after the war.

The editor of both was the crusading Y.K. Chu (朱耀渠), whose Chinese pen name was Zhu Xia (朱夏). Born in Guangdong Province, Chu attended the Baptist-run Pui Ching Academy in Guangzhou, where he learned English and developed an interest in journalism. Chu came to America in 1927 to attend Haverford College as a journalism major but dropped out during his sophomore year, likely for financial reasons. Eventually he found his way to New York, where he took over the editorship of the politically independent Shangbao from founding editor Thomas P. Chan, who appears to have quit the job after feuding with the editor of a rival paper and receiving a severe beating.

Y.K. Chu became well-known beyond Chinatown when he took on the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (CCBA), which collected dues from and acted as a quasi-government for all the city’s Chinese. After the New York Board of Aldermen proposed new hand laundry regulations aimed at driving the Chinese out of business, Chu demanded that the CCBA earn its dues by fighting the ordinance. But the CCBA did nothing, and an infuriated Chu then helped organize the Chinese Hand Laundry Alliance of New York, which fought successfully to overturn the regulations.

In the process, Chu’s paper accused the CCBA of “exploiting” (剥削) the laundrymen, and the CCBA sued Chu for libel. The Tammany Hall political machine, which had close connections to the CCBA, the local branch of the Guomindang (Chinese Nationalist Party), and one of the rival papers, controlled the courts and made sure that the CCBA’s chosen translator explained to the jury that Chu had accused the CCBA of “robbing” or “cheating” the laundrymen. Other irregularities characterized the trial, including the court’s decision to exclude all evidence that Chu offered in his defense. Unsurprisingly, the jury found Chu guilty, and the judge slapped on injunction on Chu that forbade him from criticizing the CCBA in his paper for three years.

A believer in the First Amendment, Chu fought back. First, with the help of publisher Virginia Howell Mussey, he released Chinatown Inside Out, a sympathetic 1936 book about Chinese American life that exposed the CCBA’s problems and celebrated the community’s regular people. To avoid violating the court injunction, Chu wrote the book under the pseudonym Liang Gor Yuen, a Cantonese pronunciation of “liangge ren” (兩個人), meaning “two people”–Chu and his publisher. Chu also fought back through the courts, convincing the New York Court of Appeals to overturn his conviction in early 1937. People v. Yui Kui Chu (273 N.Y. 191) remained an important precedent for decades in cases involving libel, especially in the foreign language press.

A believer in the First Amendment, Chu fought back. First, with the help of publisher Virginia Howell Mussey, he released Chinatown Inside Out, a sympathetic 1936 book about Chinese American life that exposed the CCBA’s problems and celebrated the community’s regular people. To avoid violating the court injunction, Chu wrote the book under the pseudonym Liang Gor Yuen, a Cantonese pronunciation of “liangge ren” (兩個人), meaning “two people”–Chu and his publisher. Chu also fought back through the courts, convincing the New York Court of Appeals to overturn his conviction in early 1937. People v. Yui Kui Chu (273 N.Y. 191) remained an important precedent for decades in cases involving libel, especially in the foreign language press.

Because of Chu’s relationship to the Laundry Alliance, which grew increasingly leftist after its founding and later published the China Daily News with communist support, observers and scholars have often assumed that Chu himself was a “radical.” Ironically, historians in the People’s Republic of China claim that Chu was a right-wing Guomindang activist while at Pui Ching. Whatever his activities in China, by the early 1930s Chu was a liberal whose rejection of both the Chinese Communist Party and the Chinese Nationalist Party shaped his life after the libel case. During World War II, he traveled to the Chinese Nationalist capital of Chongqing to serve on a multiparty government committee on business. He closed the Shangbao in 1944 because of the wartime labor crisis, but after the conflict he returned to publish a liberal, anti-communist semimonthly, the China Post, in the 1950s and 1960s. In the very late 1950s, he also wrote daily editorials for the short-lived New York edition of the Chinese World (世界日報), the organ of the bitterly anti-Nationalist and anti-Communist Chinese Democratic Constitutionalist Party. In his early 70s, he published a history of the Chinese in America, Meiguo Huaqiao Gai Shi (美國華僑概史/History of the Chinese People in America). He appears to have died just a few years after its publication.

Sources for this post include Chathamgreen.com, Meiguo Huaqiao Gai Shi, Chinatown Inside Out, the Chinese Weekly Review, the China Post, and Ancestry.com.

#30 Forgotten Figure

Green-wood Cemetery is one of the most beautiful spots in Brooklyn; it’s also the final resting place of many celebrities of the past, including some who have almost completely been forgotten today. One such person is George Kin Leung (梁社乾), whose cremated remains occupy a niche in the Green-wood Columbarium. A native of Atlantic City, New Jersey, Leung died in relative obscurity in Manhattan, but he had not always been so obscure.

Before World War II, the ferocious, institutionalized racism that people of color experienced in the United States prompted many young Chinese Americans to seek opportunities in their parents’ homeland. George Kin Leung was one such young man. After graduating from Atlantic City High School in 1918, Leung briefly attended the University of Pennsylvania’s dental school before immersing himself in New York’s theater world. But by 1921, he set sail for China with his half brother Edward and his niece Mae. The three planned to study Chinese and, most likely, to eventually seek work in one of China’s coastal cities. Upon arriving in Guangzhou (Canton) in early 1922, Edward and probably Mae attended feeder schools of Canton Christian College (later Lingnan University), while George apparently studied Chinese language and culture on his own.

Leung made quick progress. By 1925, he began translating Chinese literature into English, publishing the popular The Lone Swan, an autobiography of a Buddhist monk. Leung then produced the first English version of a far more significant work: Lu Xun’s The True Story of Ah Q, one of the most famous and important pieces of modern Chinese fiction.

By 1928, Shanghai’s China Press was referring to Leung as “the well-known Chinese dramatic critic,” for he was gaining considerable fame in China not only as a translator but also as an expert on the country’s opera, theater, and literature. Leung earned particular renown for explaining China and its performing arts to English-speaking foreigners. His essays appeared in most of Shanghai’s English-language newspapers, from the China Press to the North China Herald, and he routinely gave talks on Chinese theater to groups such as the Pan-Pacific Forum and the American Women’s Club. His book on Mei Lanfang, the Beijing opera superstar, also came out just as Mei toured the United States for the first time.

Leung also taught for a year or two at Hangzhou University but spent much of the 1920s moving around China studying drama. By the 1930s, however, he was comfortably ensconced in Beijing, the gracious and faded imperial capital that the ruling Nationalists had abandoned in favor of Nanjing.

The Japanese invasion and occupation that began in mid-1937 ended Leung’s golden age in China. By October, he was on a boat to San Francisco, having received an invitation to wait out the war with an endowed lectureship at Yale. The position lasted only a year, while the war dragged on far longer and eventually involved the United States. After Pearl Harbor, Leung volunteered for the Army despite being in his 40s. He served until 1944 but never returned to the land where he had built such a splendid career. The civil war and the Chinese Communist victory closed off that possibility.

Like many of the Chinese Americans who moved to China before the Japanese invasion, George Kin Leung found far fewer opportunities in the postwar United States than he had enjoyed in prewar China. For a time, he taught Chinese at Yale and gave lectures about Chinese culture in New York and Washington, DC. By the late 1950s, he was living on Rivington Street and working as a court translator. He also performed occassionally as a Chinese folk musician and singer.

Although public interest in China surged after President Richard Nixon’s 1972 visit to Beijing, the man who had introduced the greatest work of modern Chinese literature to the English-speaking world remained a forgotten man. George Kin Leung died in Manhattan in 1977, and his passing received no attention from the press.

Sources for this post include: China Weekly Review, China Press, North China Herald, immigration records and consular records at the National Archives, Ancestry.com, the New York Times, the Washington Post, the New York Herald Tribune, Baorong Wang, “George Kin Leung’s English Translation of Lu Xun’s A Q Zhengzhuan,” Archiv Orientalni 85 (2017), and Richard Chan Bing.

#29: Grim Parallels

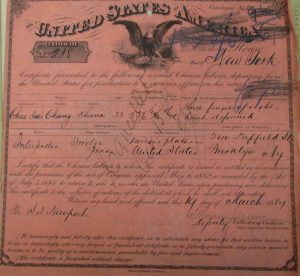

In 1882, Congress passed and the president signed an order barring all Chinese laborers from entering the United States for ten years and enshrining previous court decisions denying Chinese aliens the right to naturalize. In 1892, Congress extended the ban for another ten years and in 1902 made it permanent. The 1882 act was the first law to bar a particular nationality from immigrating; by 1924, only Filipinos, colonial subjects of the United States, could migrate to this country from Asia.

The 1892 legislation also required Chinese laborers already in the United States to “apply to the collector of internal revenue of their respective districts, within one year after the passage of this act, for a certificate of residence.” Although Chinese organizations, especially the Six Companies, organized massive resistance to registration, their resistance failed. Eventually, the vast majority of laborers registered–the first mass registration of an ethnic or national group in US history.

In 1888, Congress also passed the Scott Act, which made it “unlawful for any Chinese laborer who shall at any time heretofore have been, or who may now or hereafter be, a resident within the United States, and who shall have departed, or shall depart, therefrom, and shall not have returned before the passage of this act, to return to, or remain in, the United States.” Chinese legal residents caught abroad when Congress passed the act were never allowed to return; the US had unilaterally cancelled their return certificates, and 20,000 were permanently shut out.

Today, historians consider the Chinese Exclusion Act and the legislation related to it part of a shameful period in American history when racism guided policy. The late 19th and early 20th centuries contain many examples of this, such as the dawn of the Jim Crow era in the South, the disfranchisement of black voters there, and the terrible mistreatment of Native Americans throughout the country.

In New York City, Chinese Americans suffered as well. Those born in the US but illiterate in English grappled with literacy laws that disfranchised them. Immigration agents raided Chinese American homes and businesses, seeking seamen who had jumped ship, people who had unlawfully entered the US through Canada and Mexico, and others who could not prove their right to be in the United States. This kind of repressive enforcement was not only racially targeted, but it also encouraged vindictive residents of all backgrounds to anonymously report to immigration officials any Chinese they did not like. A tipster turned in William Chung, then living in a Bronx laundry, in 1915. Chung had actually been born in the United States but did not have any papers with him to prove it; the Immigration Service only released him several months later, after he established his citizenship by finding documents that positively identified him. The episode was a frightening reminder to Chung and his peers that as Chinese Americans, they could always face anonymous, racially-based harassment.

At times, the political climate also encouraged immigration enforcement officials to abuse their power. In the 1950s, politicians and officials within the State Department used fears of communist China to encourage harsher immigration enforcement in the United States. During a nationwide crackdown on alleged Chinese immigration fraud in 1956, FBI agents stopped ethnic Chinese in Chinatowns across the country and demanded proof of their right to be in the United States. In New York, the crackdown empowered right-wing community leaders with ties to the Nationalist regime on Taiwan and discouraged left-wing and moderate political activism for many years. In other words, immigration agents essentially served as enforcers for a repressive political group.

Sadly, the current administration seems bent on a return to this era. President Trump’s hastily issued executive order barring refugees, migrants, and even green card holders and dual citizens from seven Muslim majority countries recalls the worst episodes of racism in our immigration history. Courts around the country have now stopped its enforcement, but the president seems bent on finding other ways to push American immigration law and practice back to its worst period.

#28 Midtown East

Between 1905 and the 1920s, numerous

Japanese art goods, import-export, and housewares businesses clustered on the southern border of today’s Upper East Side in Midtown East. The shops included the importer S. Kuwayama at 114 E 59th St., the Japan Art Shop at 34 E 59th St., and the Nippon China Company and Katagiri Brothers at 224 E 59th St.

Katagiri became the first Japanese goods firm to set up shop in the district and may have followed the Japanese Christian Institute, which purchased a building at 330 E 57th Street after the turn of the century. The Institute drew Japanese Christians to the area; many young men also boarded there while studying at Columbia and Union Theological Seminary.

Other factors made the neighborhood a good choice for business. The 59th Street Bridge (also known as the Queensboro, and today the Edward I. Koch Bridge), opened in 1909. It brought customers by car, tram, and elevated train from Queens, while elevated trains that ran along Second and Third Avenues drew residents of other parts of Manhattan.

Still, many of the shops catered less to visitors than to the growing Japanese American population of the neighborhood. By the 1920s, more than one hundred Japanese Americans lived in the compact area near the off-ramp of the Queensboro. Other Japanese residential districts featured in this blog, such as the Lincoln Square area or downtown Brooklyn, housed a largely working-class population. Midtown East, on the other hand, tended to draw white collar and professional people, including the proprietors of the Japanese art stores in the district and their sales clerks. The area was also a favorite with Japanese American artists and photographers, most likely because of its proximity to the 57th Street galleries and the Art Students’ League. The district’s Japanese residents, who generally found homes in walk-up tenement boarding houses run by other Japanese, shared the neighborhood with large numbers of Irish, Hungarian, and German Americans (the area formed the southern border of heavily German and central European Yorkville). Like their Japanese American neighbors, such people tended to be white collar workers, although hardly wealthy: most were clerks, stenographers, and small businesspeople.

These residents almost certainly shopped at Bloomingdales, whose forerunner, the “East Side Bazaar,” dated to the mid-19th century. Having finally managed to buy every plot on the block between 59th, 60th, Lexington, and 3rd, Bloomingdales opened its huge new store in 1929. In addition to Bloomies, the galleries, bookshops, and antique stores of the area drew welcome foot traffic to the Japanese businesses, especially those who sold art and porcelain. But the Depression forced a number of them to close. By the mid-1930s, most of the Japanese American residents had also begun to migrate to other neighborhoods, particularly the Upper West Side and Morningside Heights.

When Japanese Americans from the West Coast resettled in wartime New York, they found Katagiri and the Japanese Christian Institute still open in Midtown East but almost no other trace of the old community there. For a few years, the Institute became a social center for the “resettlers,” but after the war it merged with another Japanese American Christian organization and sold its 57th Street property to a real estate developer. A postwar boom in interest in Japanese housewares and art goods drew a few new businesses and the famous S. Yamanaka gallery to the district in the late 1950s, but they didn’t last. Today, the area is known for its design and decorator showrooms. Only the venerable food and housewares dealer Katagiri remains as a reminder of the former Japanese American presence in the neighborhood.

Sources for this post include the New York Times, the New York Tribune, the New York Japanese Address Book (1921), Katagiri.com, and the U.S. Census for 1920, 1930, and 1940.

#27 Japanese Brooklyn

In the early 20th century, the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway did not yet cut across this somewhat unsightly section of downtown Brooklyn to the east of Cadman Plaza. The area was hardly tranquil, of course. The Brooklyn Bridge and the newer Manhattan Bridge loomed overhead, while elevated trains ran across the former and terminated at Park Row in Manhattan. Factories, including a cannery, a book bindery, and a brewery, sat among the shops and tenements of the district.

So did a Japanese branch of the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA). Between about 1895 and the mid-1930s, this area of downtown Brooklyn was home to a sizable Japanese American community, the only concentration in the borough until World War II. Most Japanese American New Yorkers in the prewar years lived in Manhattan, clustering around the West 60s and farther north, especially Morningside Heights. But the 1910, 1920, and 1930 US censuses reported that from 200 to 250 Japanese lived in Brooklyn, and around half of these people called Sands, High, Jay, Concord, and other downtown streets their home.

The Japanese Brooklynites, most of them single men, seem to have chosen the area for its proximity to jobs and transit: specifically, the piers, the Brooklyn Navy Yard, the subways, the bridges, and the elevated trains.

The Japanese Y, first established in 1895 at 54 Sands Street, proved an early magnet for the community too. The Y was the first of its kind east of the Mississippi, because the Japanese population of the US was still heavily concentrated on the West Coast in these years. The Brooklyn Eagle reported that some of the Y’s residents were Japanese students planning to become Christian missionaries, while many others worked as salesmen in the silk companies and Japanese markets of Manhattan. By 1905, the institution had moved south to 17 Concord Street, and while some of its residents attended New York University and City College, far more worked full time as butlers, cooks, and domestic servants.

Similarly, after the turn of the century, most of the other Japanese American residents of the area were working-class people, just like their Irish, Italian, Greek, Russian, and Chinese immigrant and Filipino and Puerto Rican migrant neighbors. Like others who lived in the district, a good number of the Japanese worked at the Navy Yard, usually as stewards; others were cooks, waiters, and chauffeurs elsewhere in Brooklyn and Manhattan. A few, such as Yoshikazu and Tomi Okimiya, ran boarding houses that catered to the Japanese working men of the district, and a Japanese resident even ran the popular Navy Yard Restaurant on Sands Street.

In the 1930s, though, the Japanese population of the area fell quickly; by 1940, the number of foreign-born Japanese in the borough as a whole was less than half of what it had been in 1920. In many ways, this was an unsurprising result of American immigration policy. Because of anti-Japanese agitation on the West Coast, President Theodore Roosevelt in 1907 made a “Gentlemen’s Agreement” with Japan, whose government promised to prevent Japanese men, aside from certain categories of students and professionals, from emigrating to the United States. By 1924, the United States had also made the further entry of Japanese women illegal. Japanese immigrants could not become US citizens either (this did not change until 1952).

Such laws encouraged at least some of downtown Brooklyn’s Japanese–most of them young and single working men–to return to Japan. The Depression also hit the cooks, chauffeurs and butlers of the district very hard, because far fewer families could afford to hire them. Many Japanese domestics lived at boarding houses like the Okimiyas’ 184 High Street building, which the couple eventually sold to Matsuo and Yoshi Nara. The Naras couldn’t make it work either; by the mid-1930s, they gave up the business.

By 1940, as city officials planned the razing of much of downtown Brooklyn for Robert Moses’ program of “slum clearance” there, few traces remained of the once vibrant Japanese presence in the area.

Sources for this post included the New York Japanese Address Book (New York: Nippon Jin-sha, 1921); the Brooklyn Eagle; Ancestry.com; and the U.S. Bureau of the Census.

#26: Kips Bay

Urban renewal changed (and often devastated) many areas of postwar New York. One neighborhood that experienced almost continual transformation between 1945 and the 1970s was Kips Bay, an area on Manhattan’s East Side between East 23rd and East 34th Streets from Lexington Avenue to the East River.

Racial segregation in housing was common in prewar New York (indeed, the residential patterns of that era continue to shape the city today), and it limited not only where African Americans could live but also greatly reduced the residential choices of Asian Americans and other people not considered “white.” According to census takers, Kips Bay in 1940 was almost totally “white,” although a closer look at the census manuscript for that year reveals considerable diversity within that whiteness. Native New Yorkers of various ancestries lived side by side with immigrants from across Europe, especially Italy and Greece. A large number of people from Turkey, Armenia, and Malta also called the area home. To cater to this population, Kerope Kalustyan, an Armenian immigrant from Turkey, established in 1944 the famous Kalustyan’s specialty food store (known for many years as “K. Kalustyan’s Orient Export [sometimes Orient Expert] Trading Company”) at 407 3rd Avenue between 28th and 29th Streets.

Most of the residents of the area were poor or working class and included scores of restaurant cooks and waiters, domestic servants, and laborers. They lived in Kips Bay because, as Richard West wrote years later in a New York magazine article, the area was “a scabby neighborhood of noise, dirt, and half darkness,” the result of factories and the 3rd Avenue elevated train. Directly to the south was the Gashouse District, another area that wealthier New Yorkers avoided and that today is home to Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village.

After the war, many of the residents of Kips Bay’s tenements were able to find better housing elsewhere in the city or even in the suburbs, where so many white New Yorkers eventually moved during these years. Among those who replaced the departing white residents were people who had never been able to live in Kips Bay before, including a significant number of Asian Americans. That last group consisted of a sprinkling of Filipino and Korean Americans, as well as a large number of Chinese Americans. Likely drawn by the proximity of the 3rd Avenue El and the Lexington Avenue subway line (today’s 6 train), which linked Kips Bay to Chinatown, they moved into the neighborhood beginning in the very early 1950s. The walk-up tenements in the high 20s between 3rd and 2nd Avenues proved particularly popular with people of Chinese ancestry. A Chinese American directory from the period reported that T. Ching Ming, A.C. Choy, Yu-chin Chen, Joseph, May, and Sylvia Tuck, Tih Low Tsai, Lan Ying Hsiang, Pay Dang, Tsai Sih Tai, William Yang, and several others all moved to a single block of 28th Street. Other Chinese Americans found homes just a block or two away.

The sudden availability of Kips Bay apartments reflected not just postwar white flight from New York but also insecurity that the beginning of urban renewal in the area triggered. In the late 1950s, developers with federal funding razed the blocks between 30th and 33rd Streets, which became the Kips Bay Plaza apartments (now Kips Bay Towers). The lead architect for the project was I.M. Pei, who like many of the new residents of the high 20s had been born in China, although into far greater privilege. Still, Kips Bay’s Chinese American residents were often more middle class than the people who had lived there in the 1940s; they included a number of business owners and merchants who needed to live fairly close to Chinatown.

The closure and dismantling of the 3rd Avenue El in the mid-1950s made the area less attractive to such people. And while urban renewal grew increasingly controversial, it continued into the 1960s in Kips Bay in the form of the Bellevue South Urban Renewal Project, which resulted in the razing of many tenements east of 2nd Avenue. The construction and disruption pushed out many of the Asian Americans who had relocated there in the early 1950s, as did the proliferation of SROs in the area. A decade later, though, a new group of Asian Americans arrived in the area: immigrants from South Asia, who while mostly living in Queens, opened restaurants, groceries, and shops on the same strip of Lexington where Kalustyan’s had relocated. Today, the area is still known for its South Asian restaurants, sari shops, and sweet and spice stores, many of them established in the 1970s and 1980s.

Sources for this post include: Sino-American Publicity Bureau, Chinese Directory of Eastern Cities (New York: Sino-American Publicity Bureau, 1954); Richard West, “The Building,” New York, March 23, 1981; New York Times; https://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/bellevue-south-park/history; Robert Caro, The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York; Joshua Zeitz, White Ethnic New York; Joshua Freeman, Working Class New York; Ancestry.com; and the Social Explorer database.

#25: Brooklyn Consulate

This lovely old apartment building, at 300 Eighth Avenue in Park Slope, Brooklyn, was once home to the Chinese Consul General in New York, Samuel Sung Young ( 熊崇志). A native of San Francisco, he was the son of Chinese immigrant clergyman Walter C. Young and Ah Tim Young, a Hong Kong native. After high school in San Francisco, Samuel Young graduated from the University of California, Berkeley, but soon after his graduation, he left for China. Like many young, well-educated Chinese Americans of his generation, he had very few job opportunities in the United States due to racial discrimination.

In China, Young enjoyed considerable success. Initially, he worked for the Guangzhou (Canton) Board of Education, and it was during this period that he met and married Lucy Woo, a Hong Kong resident. In 1908, Young accepted a post as president of the Tangshan Railway and Engineering College, located in the city of Tangshan east of Beijing. The 1911 revolution that ended the Qing dynasty and inaugurated the Republic of China appears to have cut short Young’s career at the college. In 1912, he moved to Tianjin, where he participated in a number of commercial enterprises related to mining and occasionally traveled to the United States. Eventually, he accepted a post as secretary in the Foreign Ministry at Beijing (his brother David Young also joined the foreign service).

Young’s career eventually took an unusual twist. In 1926, the National Revolutionary Army, which drew members from the Guomindang (the Chinese Nationalist Party), the Chinese Communist Party, and allied forces, -launched the “Northern Expedition” to unite China by defeating the warlords who controlled the central and northern parts of the country. By August 1927, the Guomindang was in control of most of the south and the lower reaches of the Yangzi River, although the Nationalists had fractured due to General Chiang Kai-shek’s bloody purge of Communists that spring. While the Guomindang forces regrouped, the canny warlord Zhang Zuolin tightened his grip on Beijing, meaning he controlled the internationally recognized government of China. And in August 1927, he appointed Samuel Sung Young to be China’s consul general in New York City. That same month, the “Southern Government” under the Nationalist regime at Nanjing appointed Frank Lee Chinglun, a New York native, to be its representative in Washington, DC.

Samuel S. Young left his wife and children behind in China when he sailed to the US. Arriving in New York, he must have lived briefly in another apartment or hotel before moving into 300 8th Avenue; press accounts date the building’s completion to 1928. By 1930, though, he was comfortably ensconced in the building in a $60 a month apartment–paid for by his new employer, the Chinese Nationalist regime that had ousted Zhang Zuolin from Beijing. The Guomindang had little money to spare for prestigious accommodations in Manhattan; the other residents of 300 8th Avenue include clerks, teachers, and minor civil servants. Except for Young, all of the other residents were white. Perhaps his status as a diplomat protected him from the housing discrimination that other nonwhite New Yorkers faced.

During his tenure as Chinese consul-general in New York, Young attempted to improve the image of Chinese Americans in the city. He also played a pivotal role in brokering a truce between New York’s two major tongs, the On Leong Tong (which Frank Lee’s father had helped found) and the Hip Sing Tong. Young probably looked back on his years in New York with fondness after the Chinese government posted him to Mexico in 1931. There, he had to grapple with the violent fallout from a major anti-Chinese movement that had deep popular and political support. Still, he stayed in the post until 1941.

After the Nationalist regime fled to Taiwan in 1949, Young and his family chose to resettle in Hong Kong. There, Young worked as the bursar of St. Paul’s Educational College until his retirement in 1954. Samuel S. Young died in Hong Kong in 1958, at age 74.

Sources for this post include The New York Times, the South China Morning Post, the National Archives, Ancestry.com, and the Christian Science Monitor.

#24: On Broadway

In early 1930, theater-goers in New York City enjoyed an unusual oppor-tunity: Mei Lan-fang, the most famous Peking opera actor in China, visited the city as part of a US tour to showcase his art and to make a case for his homeland’s culture. Mei’s specialty was young female roles, which male actors routinely played in Chinese operas well into the 20th century. He and his troupe began their New York run in February 1930, performing at the 49th Street Theater (left), which producers J.J. and Lee Shubert had built in 1920. The theater was torn down in 1940, however, and today 235 W 49th is home to the Pearl Hotel (right).

Although Peking opera is stylistically and musically quite different than Western operas and American musical theater, New Yorkers packed Mei’s performances, and scalpers charged several times their tickets’ face value. According to theater scholar Nancy Guy, Mei’s close collaborator Qi Rushan had studied the kinds of Peking operas that most appealed to the foreigners who saw them in China, and Mei, Qu, and their opera company geared their performances to appeal to American audiences. Each night, Soo Yong, a Hawaiian-born Chinese American woman who was a veteran of Broadway, introduced and explained the evening’s program in English. Although Mei sang entirely in Chinese, Qu’s approach worked: audiences were enthralled. Brooks Atkinson, theater critic of the New York Times, gushed that “the chief impression is one of grace and beauty, stateliness and sobriety, of unalloyed imagination.”

Mei certainly appreciated the warm welcome he received, and his humility and public statements about wishing to study American drama while in the United States won fans as well. So did his high-profile meetings with actors such as Charlie Chaplin. But no one was happier about the success of Mei’s American tour than its major sponsor, the China Institute.

Founded just a few years earlier in 1926, the China Institute included prominent Americans and Chinese, as well as a few Chinese Americans (such as New Yorkers Ernest K. Moy and his sister Katherine Moy Chen), on its board. The group’s purposes included the promotion of Chinese culture in the United States. At the time, many Americans saw China as a poor, backward, and politically chaotic land with little to offer the rest of the world. Movies, magazines, and books of this era routinely portrayed Chinese as either sinister or pitiful. The China Institute sought to change this image. Indeed, this was a small part of a far larger campaign by Chinese intellectuals, students, and others to help to improve the way the major world powers treated their homeland.

The popularity of Mei Lanfang’s New York performances delighted the China Institute’s members. Although Mei originally planned a limited run of performances, he bowed to popular demand and in early March moved down to the National Theater, today known as the Nederlander Theater, for another run.

Coincidentally, one of Mei’s competitors for New York theatergoers’ interest was Tokujiro Tsutsui, whose troupe of twenty-nine actors specialized in modernizing older forms of Japanese drama. The Japanese group arrived in New York in early March 1930 and followed Mei’s lead in at least one way: like Soo Yong, Michio Ito, a Tokyo-born dancer then living in New York, explained the performances in English for the audiences who attended the nightly shows at the Booth Theater, just a few blocks north of the National. Ito, a friend of Martha Graham and a pioneer of modern dance, had also adapted and helped direct the troupe’s performances.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, critics compared the two groups of “Oriental” actors. Critic John Martin chastised Ito for the production, and while Brooks Atkinson found some of the Japanese troupe’s swordplay diverting, he panned the rest of its performance in a biting comment tinged with racism: “At best it is Oriental drama that is coming down the main highway of the Occidental theater, and has not progressed very far.” Atkinson far preferred the “ancient” style he attributed to Mei Lanfang–a telling detail that suggested the kind of orientalism common in America at the time.

One group was largely absent from Mei’s performances: Chinese New Yorkers. Outside of the wealthiest and most prominent, few could afford to see Mei or understand the dialect in which he sang. Instead, they continued patronizing their own local Chinese theaters, where traveling troupes and local actors performed for far lower prices than Mei commanded on Broadway.

Sources for this post include: The New York Times; Nancy Guy, “Brokering Glory for the Chinese Nation: Peking Opera’s 1930 American Tour,” Comparative Drama 35:3-4 (2001-2); Yunxiang Gao, “Soo Yong (1903-1984): Hollywood Celebrity and Cultural Interpreter,” The Journal of American-East Asian Relations 17:4 (2010); MichioIto.org; and ChinaInstitute.org.