The following is a distillation of key concepts in Mulvey’s “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” I hope this helps.

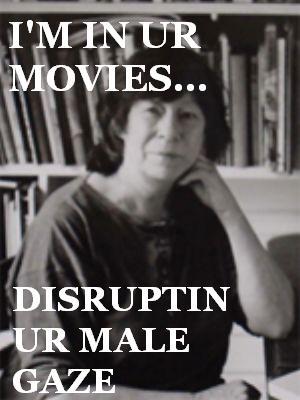

Laura Mulvey, “Narrative Cinema and Visual Pleasure,” 1973.

Mulvey appropriates psychoanalysis as a “political weapon” in order to expose ways in which the “patriarchal unconscious” structures film form and the way we experience it.

Woman is the bearer, not maker of meaning in a patriarchal, phallocentric symbolic order. The paradox of phallocentrism is in that it depends on woman (as lack) to provide meaning and order, to give symbolic meaning to the phallus (the yin needs its yang) – phallus also signifies threat of castration (woman’s supposed desire to “make good the lack”).

There is no lasting place in phallocentric order for the woman: she exists only to symbolize lack, threat of castration (by lack of phallus, male power) and to bring children into the symbolic order –to reproduce it. In patriarchal culture, woman is only the signifier of the “male other” – of that which the male is not, his binary opposite.

According to Mulvey, psychoanalysis allows a way to interrogate patriarchal order from the inside, “to fight the unconscious structured like a language” – provides a way of understanding the frustrating predicament of woman within the patriarchal order.

The unconscious (shaped by the dominant order) structures looking, visual pleasure; film poses questions about the way this works. Hollywood film coded “the erotic” into language of dominant culture. An alternative to this coding is possible in avant-garde, alternative cinema but as a counterpoint to Hollywood. Mulvey wants to rip apart this coding of beauty, erotic pleasure, to destroy it: “It is said that analyzing pleasure, or beauty destroys it. That is the intention of this article.” She wants, in part, to “conceive new language of desire.” She sees a thrill in this sort of thing.

Two contradictory aspects of pleasure of looking in film: 1) scopophilia, 2) identification.

1) Scopophilia: scopophilic instinct: pleasure in looking at another as sexual object. Audience as voyeurs, isolated from images on screen and one another – audience as looking in on a private world (by way of narrative conventions, etc.). The spectator represses own exhibitionism and projects desire onto screen performer. (This is the separation of subject’s “erotic identity” from object on screen.)

2) Identification: ego libido; related to Lacan’s mirror stage; spectator identifying with an image on screen, gap between image and self-image. Mulvey relates image to first articulation of “I,” subjectivity; constitution of ego, narcissism. (Identification of ego identity w/ object on the screen – subject seeing his/her like.) Paradox: look can be pleasurable in its form but threatening in its content – woman is an active threat of castration is “crystallization” of this (desire born of language and can transcend instinct (scopophilia) and libido (identification), but returns to traumatic source, to the fear of castration).

Active/male; passive/female. Image of woman (passive) is “raw material” for the looking of man (active). Woman as exhibitionist: is simultaneously to be looked at and displayed – coded to connote “to-be-looked-at-ness.” Woman as “alien presence” in many mainstream films – only there to be looked at, breaks diegesis. Woman as erotic object for 1) male characters in the movie and 2) for the spectator – there is a shifting tension between the two looks. Man in the story is the bearer of spectator’s gaze. Lead male character serves as surrogate for spectator’s look – conferring a sense of omnipotence: “so that the power of the male protagonist as he controls events coincides with the active power of the erotic look.” Man as “figure in a landscape” – demanding presence in space, commanding “stage of spatial illusion” while woman is often “cut up,” despatialized (close-ups of body parts, etc.) – not occupying the virtual landscape of the film.

Big problem in the figure of the woman: Since woman de facto signifies sexual difference, a lack of a penis, the threat of castration, “unpleasure, she threatens to destroy unity of the diegesis: “Thus the woman as icon, displayed for the gaze and enjoyment of men, the active controllers of the look, always threatens to evoke the anxiety it originally signified.” (This is also the contradiction inherent in the structures of looking: as is, the image of woman threatens diegesis, imaginary world of the film asn comes off as an “intrusive, static, one dimensional fetish.”) To “escape,” to avoid castration anxiety, to maintain diegesis, the male unconscious can take one of two avenues:

1) voyeurism: going to source of anxiety (“investigating the woman, demystifying her mystery”) combined w/ devaluation, punishment, or saving “the guilty object” This is typical of film noir, she says – has sadistic element in asserting control, judging, punishing.

2) fetishistic scopophilia: disavowing castration altogether by fetishizing the figure of the woman (or substituting fetish object), taming it, making it reassuring, satisfying in itself.

Sternberg’s films with Marlene Dietrich are a good example of fetishistic scopophelia: no identification with male star – all about looking at Dietrich as fetish object. There is little or no mediation of spectator’s gaze through the male character. Male hero does not see, but the spectator does.

Hitchcock’s films, on the other hand, rely on voyeurism quite a bit: viewer essentially sees through the male protagonist, assumes his subjectivity, his looking. In Rear Window, for example, Jimmy Stewart’s “Jeffries is the audience.” Erotic element is in looking; his sexual relationship with Grace Kelly’s Lisa (who is already an exhibitionist) is only re-ignited when she crosses over and becomes the object of his gaze. Hitchcock makes audience voyeurs as much as the lead protagonist: “The audience is absorbed into a voyeuristic situation w/in the screen scene and diegesis that parodies his own in the cinema.” Mulvey offers examples from Marnie and Vertigo as well.

All this business – this structure of pleasure in looking – is not inherent to the film medium but to prevailing film form in its aping of the male unconscious. The camera is an instrument beholden to the neurotic needs of the male ego. Spectator can’t get distance from the image on the screen because fetishization steps in as soon as the erotic image shows up and works to conceal the threat to the “spell of illusion” posed by the unmediated fetish object; the audience look is frozen, fixated.