Background Information

From 1979 to 2015, China implemented one of the most sweeping population control measures in modern history — the one-child policy. This government-enforced limit on family size was aimed at curbing China’s rapid population growth, which was seen as a threat to the country’s economic development and environmental sustainability. Though the policy officially ended years ago, its impact remains deeply embedded in Chinese society. Families were shaped by it. Generations were defined by it. And the psychological, demographic, and social consequences are still unfolding.

Origins: Why the policy was introduced

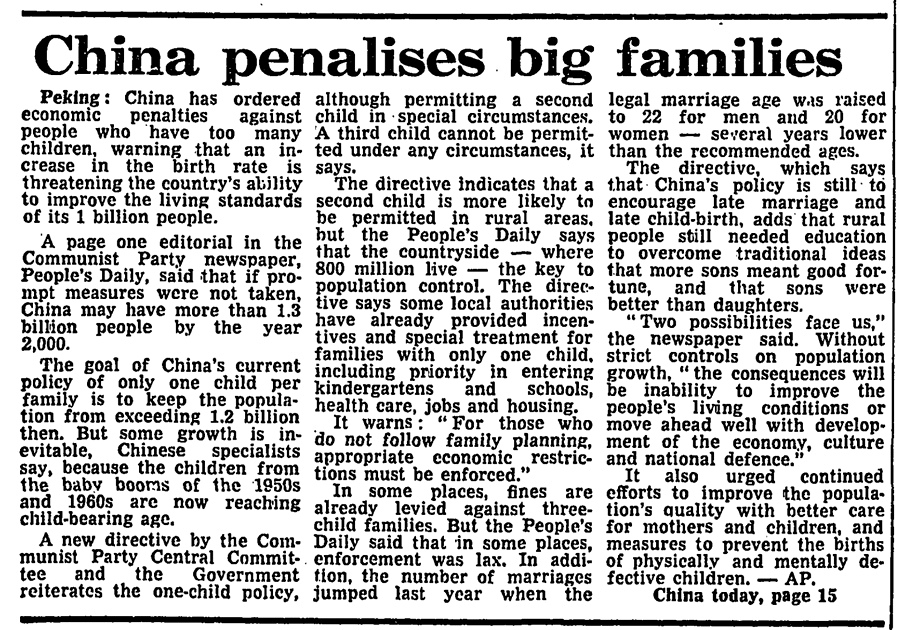

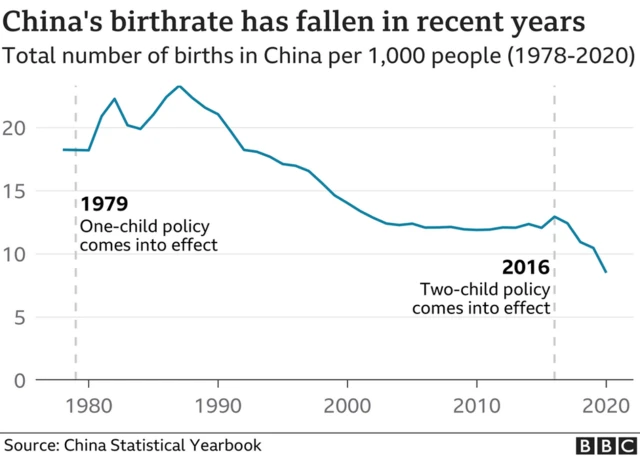

In the decades following the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, Mao Zedong encouraged high birth rates, believing that population growth would strengthen the nation. By the 1970s, however, that philosophy had shifted. China was facing food shortages, rising unemployment, and overburdened infrastructure. The government determined that population control was necessary to meet its modernization goals. Initial efforts to encourage delayed marriage and fewer children evolved into a strict policy: most families would be permitted only one child. Introduced nationwide in 1979, this policy was enforced through an array of incentives and punishments; including financial penalties, job loss, and in some cases, forced sterilizations and abortions.

Look at the Daily Life

Life under the one-child policy was marked by a complex mix of pressure, propaganda, and fear. Urban families were closely monitored by neighborhood committees and local officials who were held accountable for population control targets. State slogans such as “Have fewer children, live better lives” were displayed across cities and villages. Parents who obeyed the policy received rewards such as priority housing or better job placements, while those who defied it could face heavy fines or worse. For many, the policy was not just a rule but a constant presence that influenced decisions about marriage, healthcare, employment, and privacy. Families that had second or third children sometimes hid them, sent them to live with relatives, or went without registering them with the government, depriving those children of access to education, healthcare, or legal identification.

Gender Imbalance and “Missing” Girls

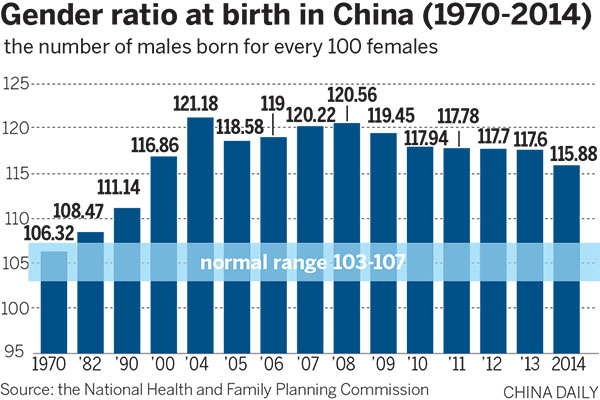

One of the most severe consequences of the policy was the acceleration of a gender imbalance in China. Due to a longstanding cultural preference for sons because they were seen as caretakers of elderly parents and carriers of the family name. Many families chose to abort female fetuses or abandon baby girls. This resulted in what demographers have termed “missing girls,” with millions of women unaccounted for in the population. By the early 2000s, the ratio of boys to girls in China had risen to one of the highest in the world, peaking at around 120 boys for every 100 girls in some provinces. This demographic imbalance has led to broader societal issues, including a surge in bachelorhood, human trafficking, and mental health concerns for men unable to find spouses.

The Psychological and Social Burden of Being an Only Child

China’s one-child generation, sometimes called “the loneliest generation,” grew up with intense expectations. As the sole child in a family, they were the focus of both parental pressure and national propaganda that cast them as the future of the country. These children were often referred to as “little emperors” being pampered and protected, but also burdened with the responsibility of caring for two parents and four grandparents. The so-called “4-2-1” family structure (four grandparents, two parents, one child) placed enormous pressure on this generation as their parents aged. Without siblings to share the emotional and financial responsibility of elder care, many only children now face the reality of supporting an entire extended family alone. This came with huge mental stress and pressure and could start as early as middle school.

Eventual Repeal of the Policy and the Legacy

Over time, the Chinese government acknowledged some of the harsh realities brought about by the one-child policy. In rural areas, where traditional reliance on sons for farm labor persisted, some families were permitted to have a second child if the first was a girl. Ethnic minorities were also often exempt from strict enforcement. Still, millions lived under tight restrictions. In 2013, the government allowed couples to have a second child if one parent was an only child, and in 2015, it officially ended the policy altogether, replacing it with a two-child policy. By 2021, a three-child policy was introduced. However, due to the high cost of having more children with the economic pressures, many young couples are unwilling to expand their families even after the policy was repealed. Birth rates continue to fall and this will be a long-term effect of the one-child era. The one-child policy did succeed in slowing China’s population growth with estimates suggest it prevented between 200 to 400 million births. But the human cost was huge. It affected the most intimate aspects of people’s lives: how they formed families, how they raised children, and how they aged. Its legacy is not just demographic, but deeply personal. Today, China faces a shrinking workforce, a rapidly aging population, and a generation of people born during the one-child policy. The policy is apart of history, but its consequences and effects still impact the lives of those who lived through it.