We’ve passed along our research and the design of the first scenario and asked our collaborators to take a look, so while we’re waiting for some feedback, Hamad and I decided to try to play some games ourselves to see how we might be able to adapt them for this resource.

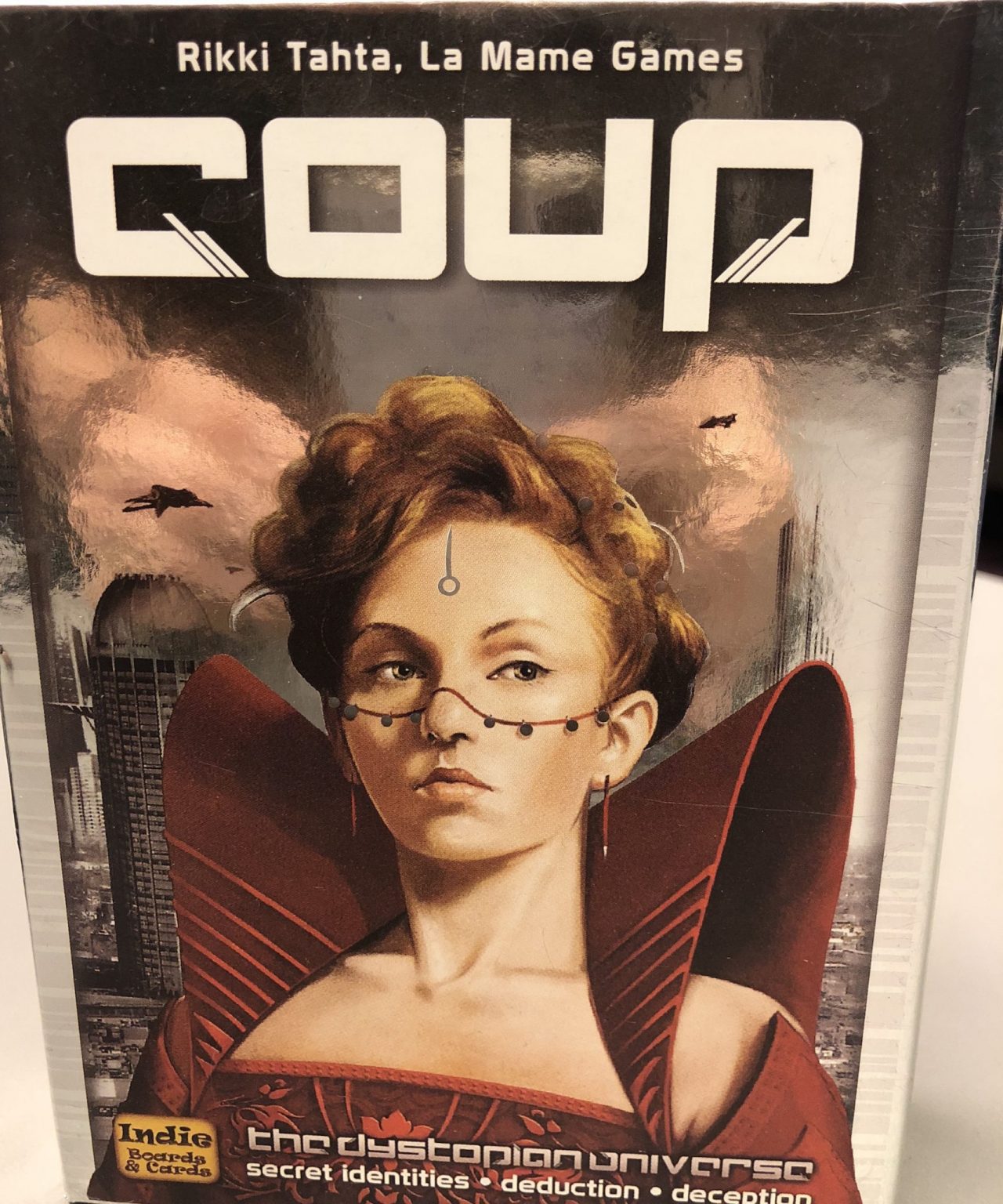

A few weeks ago, Allison (the CTL director) told us that her son had been playing this card game a lot over the summer. She offered to bring it in to the center so that we could try it out. It’s called Coup: The Dystopian Universe. The premise is that in the “not too distant future,” the government has been taken over by “a new ‘royal class’ of multinational CEOs'” (sooo, maybe the future is now?). The players are all powerful government officials who are fighting their way toward absolute power by diminishing the influence of rival officials.

In each round, each player gets two “influence” cards with characters on them who have different kinds of power. Some influences can block assassinations. Others can prevent a player from collecting money that they need to perform certain tasks. The object is to knock out other players’ influences, to gain other influences, and basically to become as powerful as possible.

What was really interesting about the experience of playing the game was how long it took us to understand what was going on. There were a lot of characters and rules! Once we actually started playing, though, the rules started to make much more sense. It was easier to dive in and just figure out how we were making mistakes rather than reading the rule book.

This reminded me of active teaching and learning. Rather than explaining everything that a student needs to know before they start using a concept, in an active learning classroom, it’s important to get the student engaged with trying out the material as soon as possible, even (and maybe even especially) when they don’t totally understand it yet. The game book became a guide to help us when we needed to know something rather than a body of content that we needed to completely master before we started playing.

It was also a good reminder of how vulnerable it can feel to learn something new! I kept making dumb strategic moves: partly because I wanted to see what would happen, but mostly because I didn’t really understand what I was doing. Even though there were literally zero stakes, I was surprised to find that I felt a little embarrassed when Hamad assassinated me and amassed a ton of influence (he is a Coup pro). I wanted those gray coins, dangit!