Over the last two weeks, Hamad and I have started to write character descriptions for the players in the game.

Most of the game’s characters are real people from history, so we’ve turned to biographies, autobiographies, interviews, profiles, obituaries, and material on the digital archives to reconstruct a brief and descriptive portion of the person’s life. Because of the way that we needed the factions to be balanced so that the voting members could genuinely decide whether or not open admissions should pass and the decision could genuinely go either way, we also needed to fictionalize some characters who were less decided or even apathetic about the decision (but who may not have found it necessary or appealing to write about their apathy).

Both of these profile types can be challenging to write for their own reasons. Deciding which details from the life of a historical person are important to highlight for the purposes of this game can cause us to worry that we’re leaving too much out or that we’re choosing the details that tell a very specific story. But writing a profile of a fictional person can feel daunting too: are these characters fully developed people? Are we relying on stereotypes and assumptions?

This exercise has helped me to consider the potentially complicated dynamics of the role of empathy in this game. To be clear, there are some characters in this game who I don’t want to empathize with. I also think empathy is a vexed concept: marginalized people are constantly confronted with the perspectives and opinions of people in power. Being acquainted with those perspectives can be a survival and navigation technique, but not necessarily a choice. And yet, the door doesn’t have to swing in both directions — there’s nothing that forces someone with power into understanding the perspective of someone without it.

And yet, in writing these character descriptions, it can be so easy for me to just make a caricature of a person without considering all of the complex factors that influenced the things that they wrote and thought — especially when I disagree with them. It’s a lot harder to build in some dimension. How could this person have arrived to a particular conclusion? Is it as simple as I’m making it out to be? Did X lead to Y? Would the historical people we’re characterizing recognize themselves in our characterizations? Maybe, and maybe not.

This all leads me to wonder how we’ll help faculty (and especially newer faculty) to navigate the “hot” classroom moments that could arise when students play this game, and how to do this with care. This doesn’t feel like something that will just “happen naturally” without some thoughtful pedagogical structuring.

I’m wondering, too, if playing a character with a massively different perspective than the one that you hold in real life will help a student to understand that perspective in greater complexity, or if it will just feel minimizing and damaging and violent to have to play a character who may have devalued your humanity or your right to access a quality education.

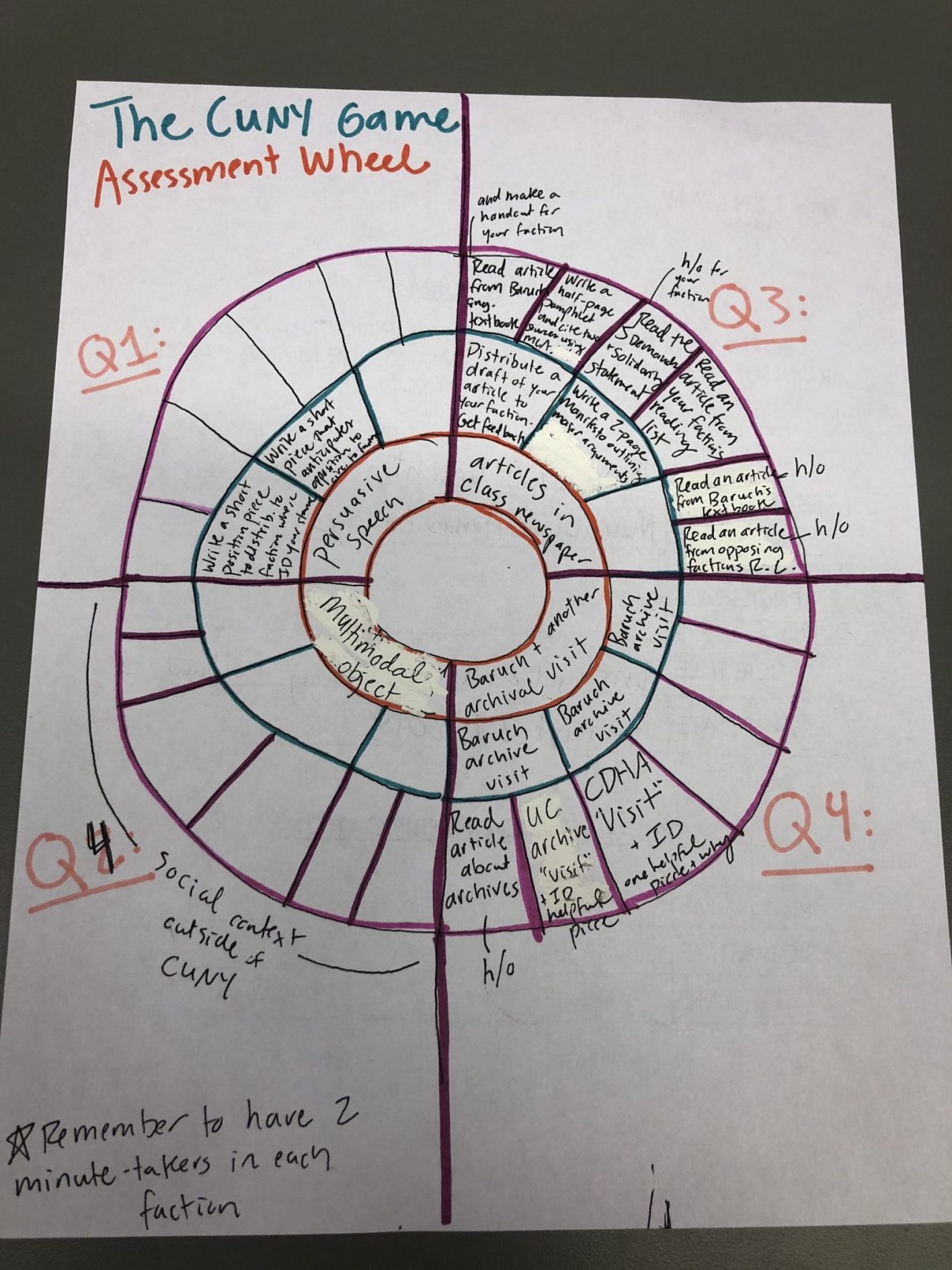

I will return to this soon, but now I’m off to collaborate with Hamad on a network of the connections that are starting to emerge between characters. Stay tuned…!