There are beautiful and captivating soliloquies within Hamlet that provide thought provoking imagery. Hamlet’s speeches alone stand out among the rest for obvious protagonist reasoning, but the most iconic part of them are the rhyming couplets he always ends with. Once you weed out the lunatic jargon, and assess the point of his rantings, he always brings it home with two rhyming lines that beautifully summarize his sentiments, as when he says, “I’ll have grounds/ More relative than this. The play’s the thing, / Wherein I’ll catch the conscience of the King” (2.2.615-17). With the same number of syllables in both lines and fitting the rhyming scheme of a couplet, these two lines provide a clarity to his mad rants.

A couplet is usually inserted by an author to provide entertaining and make the content of the speech more interesting. I believe it is inserted by Shakespeare to provide clarity to the audience as well as a brief relief from some of the difficult terminology and symbolism Hamlet uses. It provides relief for the audience as well as the main character himself. His inner turmoil, which spills out into soliloquies that aren’t exactly lucid at times, always come to fruition with the insertion of a couplet.

Hamlet’s battle with his love for his mother and the betrayal he feels his father did not deserve with her new marriage is a tough one for him. At times, the audience does not know if he means to spare her as he sheds light on his thoughts with the couplet, “How in my words somever she be shent, / To give them seals never, my soul, consent!”(3.2.406-407). This indicates that Hamlet’s defeat of the King will absolve his mother of any sin he feels she has committed, but he still very much loves her and does not wish her harm, only absolution.

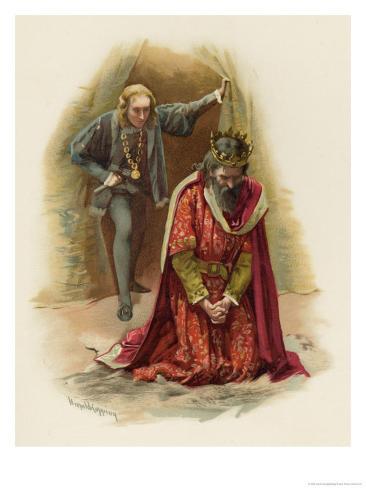

We see these lucid couplets again and again, bringing Hamlet’s rampant thoughts full circle and alleviating the reader of difficult and at times confusing verse style. One of the last times Hamlets speaks in couplet is “To hide the slain? O, from this time forth, My thoughts be bloody, or be nothing worth!”(4.4.65-66), as he decides to take action against the wrongdoings towards his late father. Inspired by the blind but brute force of soldiers with no personal vendetta, simply carrying out someone else’s orders, Hamlet gathers up the courage to go through with his plan. The couplets dissolve from here and the audience does not need a few lines to inspire excitement because the play’s ending is already full of action. In fact Hamlet’s last lines in the play before his eminent death are quite simple and emphasize the importance of telling someone’s story. He ends his life and rants with “- the rest is silence” in act 5, scene 2, indicating that he is all out of words and it is someone else’s turn to relay his message.