Although Shakespeare had crafted many characters and numerous plots, he still managed to tie them together. Hamlet and King Lear, for instance, both touch on the idea of succession. In Hamlet, Claudius murdered King Hamlet to seize the throne. In King Lear, the king passed down his kingdom to the wrong daughters. Both plays questioned the legitimacy of succession.

Perhaps Shakespeare found interest in exploring the idea of succession because of what was happening in England at the time. In the years between the writing of Hamlet and King Lear, the crown had been passed down from the “Virgin Queen” to James I. Towards the end of Elizabeth’s reign, the queen put a ban on the discussion of succession because she had neither married nor had children. Shakespeare, nonetheless, embedded the topic into his plays.

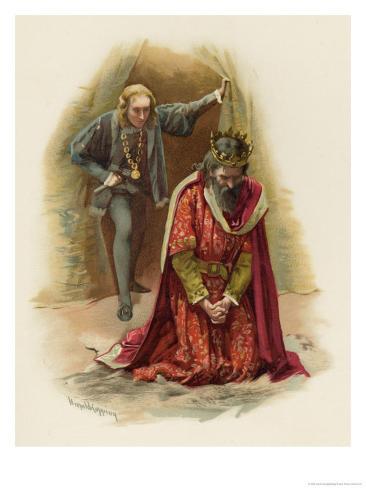

In both Hamlet and King Lear, succession had taken a turn for the worse. In Hamlet, Claudius’ rise to the crown was blatantly illegitimate. By killing his brother, Claudius not only had the opportunity to marry his wife but to also derail prince Hamlet from the path to becoming king. This situation stands in stark contrast with Harry’s situation in Henry IV, in which Harry suddenly had to assume the role of the “second-in-line.” To fix the illegitimate succession, Hamlet turned to destruction. Almost everyone died, except for Horatio who lived on to tell the story. Succession inevitably went on but beyond the scope of the play.

In King Lear, the king sought to fix his misjudging of character. Lear, like Elizabeth, had been on the throne for a long period of time. Lear was concerned with preserving his legacy. However, he was blindsided by the flattery of his daughters Goneril and Regan. The king turned all that he had into nothing.

Ann, since only Hamlet knows that Claudius killed his father, there would be no reason for his ascent to the throne to be thought illegitimate. Primogeniture was not the rule in Denmark and the second scene of Hamlet makes clear that Claudius has established himself without incident. It’s Hamlet who looks out of place. That being said, of course you’re right that issues of succession and rightful governance obsess Shakespeare and many of his contemporaries as well.

Ann,

I agree: succession is definitely at the heart of both Hamlet, King Lear. But I think the issue of filial obligation that you mention is a different creature altogether, and the way that it affects characters in each play is very different. For instance, in Hamlet, one could say that the thing that motivates Hamlet to plot against Claudius is the familial obligation that he feels towards his father. Before his meeting with the King’s Ghost, where he learned the details of his death, Hamlet expressed that Hamlet Sr. had not been mourned for properly, and that this was a disgrace to his honor. In this way, one can argue that Hamlet is motivated by a genuine filial obligation to his father, by the idea of honoring his father.

This same idea of honoring a parent can be seen in the first scene of “King Lear,” where Lear asks his daughters to vocalize their love for him (essentially, he is asking his daughters to honor him in a public setting), but I think that filial obligation plays a much less prominent role in how each sister responds–especially in the case of Goneril and Regan. Both Goneril and Regan extol their love for Lear because they understand that doing so will result in a piece of the kingdom: they honor Lear for political gain (“succession”), and not out of filial obligation. Thus, Goneril and Regan are much more concerned with issues of succession than Hamlet is, and I think that they way that each of these characters “interact” with their parents sheds more light on the idea of filial obligation than it does on succession.