At the Center for Teaching and Learning, we often work with instructors who are eager to try incorporating more active learning techniques into their classes. However, teaching in this way can present some challenges.

Below, you’ll find some frequently asked questions about incorporating active learning along with some resources for explaining the strategies to your students, coping with an increased assessment load, and dealing with resistance or disinterest.

Still have questions? Feel free to make an appointment to speak with a CTL consultant by contacting [email protected].

Isn’t “active learning” just a new buzzword? Where did active learning come from?

The term “active learning” is having a media moment1 2 3. Writers have consistently pitted active learning against its supposed foe, the lecture, and offered active learning as a panacea for regaining the student attention that has supposedly been sucked away by distracting electronic devices.

But the concept of engaged, student-centered, critical learning is not new. The binary between active learning and lectures is a false one, as lectures do not necessarily need to be passive. And while it’s true that structures of attention seem to be shifting, and devices are perhaps making this shift more visible, it’s also true that student distraction has always been part of our classroom landscape (who among us has never written or passed a note, got caught up in a daydream, stared absently out of a window, or even fallen asleep during a class?)

Since the early 1980s, educational researchers have been urging university faculty to involve students more actively in the process of their own learning rather than relying on more passive instructional models. And well before that, critical pedagogues like Paolo Freire and theorists of learning such as Jean Piaget, John Dewey, and Lev Vygotsky (among many others) agitated against models of teaching and learning that centered rote memorization and teacher-centric transmission of content, and that failed to account for the fact that learning is a social process.

Educational researchers and theorists such as Jean Anyon, Frankie Condon, Chris Emdin, bell hooks, Rochelle Gutiérrez, Asao Inoue, Stephanie Kerschbaum, Gloria Ladson-Billings, Bettina Love, Leigh Patel, Margaret Price, Ira Shor, Jesse Stommel, and Victor Villanueva—whose work focuses on issues of equity and social justice in teaching and learning across a variety of disciplines—have extended this work to help us consider how our students’ unique experiences, biases, questions, abilities, interests, styles, cultures, and languages impact the way that they learn (and the way that we teach). At the center of their work is a focus on students.

Instead of focusing primarily on information transfer, and instead of assessing learning primarily through high-stakes tests, active learning instructors seek continual “low-stakes” or “no-stakes” feedback about how students have understood key concepts. This feedback determines the pace and the direction of future instruction. But lots of things can “qualify” as active learning—not just classrooms with a game-like environment, not just “group work” and not even just making students talk to one another.

How can I encourage all of my students to participate in active learning?

Start by learning more about active learning yourself. You might read this brief introduction to active learning (external link), or some research on the effects of active learning (external link) to help with this.

Once you have a good idea about your own reasons for employing more active learning, you should talk to students directly about the benefits of using it. Instructors who explained to students the benefits of incorporating active learning in the classroom saw decreases in student resistance (Braun et al., 2017; Hayward et al., 2016). This video from the University of Minnesota highlights how instructors who use active learning in classes across the disciplines deal with framing their approach to their students.

In an active class, student participation is necessary and instructors should hold students accountable for participating. But remember: it can also be hard — especially if students come from a cultural background where participation is rare, if they’re introverted, if they’re used to a more passive model, or if they don’t understand the goal of the exercise. So:

- Know why you’re doing something.

- Let students in on your reasoning.

- Be transparent and receptive to feedback.

- Check to ensure that students have understood the instructions of the task before they begin it.

- Acknowledge that switching to a more “active” approach will take time, and that it might not happen all at once. It’s OK to add a few things every semester.

I’m new to active learning. How can I make sure that what I’m doing is working?

It might also be a good idea to conduct short, informal, anonymous surveys a few times during the course to find out what’s working and what needs to be modified.

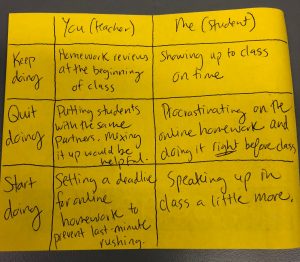

A favorite of ours is called the KQS survey. In it, students can give feedback on what they’d like for you to start, keep, and stop doing as the teacher, but they can also reflect on what THEY need to start, keep, or stop doing as students.

Here’s a picture of what a KQS survey looks like:

For more techniques designed to help you facilitate student feedback, check out this guide on sample student feedback questions from the George Washington University Teaching and Learning Center.

How can I encourage all of my students to work together?

There are several approaches to this. As with the first question, instructors should let students know that group members need to help each other learn and that they will be held accountable for their participation. From the very beginning of class, it can be helpful to try to create a community by getting students to learn each others’ names, giving them some opportunities to interact, and encouraging them to work in pairs to answer or generate questions instead of cold calling. The Centre for Teaching Excellence at the University of Waterloo offers some great suggestions for fostering community in larger classes.

In addition to fostering community, you might want to think about how to vary your groupings. It is best not to have fixed groups, and instead, to alternate who students work with, as they can become bored or demotivated by working with the same person (Cooper, 1995).

Monitoring (i.e. walking around the room and listening to what students are saying) also helps. Sometimes, students aren’t working together because they’re stuck. Sometimes, they’ve finished the problem set and they need another challenge. Listening closely to students can help you know how to group them for the next activity.

What if “strong” students don’t want to work with “weaker” students?

Research generally shows that we learn more by teaching other people. This usually makes sense to teachers: think about how well you learn the material that you’re teaching when you have to break it down and explain it to someone else.

Sharing a little about how teaching has made you understand the material more effectively, as well research that shows that “A” students typically state that helping others deepened their understanding of the material, might help students see the benefit of helping each other (Faust & Paulson, 1998).

Varying groups can also help with this problem. Sometimes, students simply feel frustrated because they’re working with the same person too often.

As a student, I loved lectures. I found doing activities (especially in pairs) to be really annoying / patronizing / boring / not useful. Why should I consider incorporating more active strategies?

A growing body of evidence shows that lectures are not “natural” or “neutral” formats for imparting knowledge. In fact, this format likely favors certain groups of students over others, as studies have shown. Thus, even if this is your favorite way of receiving information, it’s important to consider whether or not all of your students feel the same way.

That said, incorporating more active learning strategies into your classroom doesn’t mean that you have to abandon lecturing completely! Striking a balance is still important: classes that are full of only pair work or discussion can be difficult places for some students to navigate just as lecture-heavy classes can be difficult for others. Increasing and diversifying the opportunities that students have to engage with course content will help to ensure that your class reaches more students more effectively.

I teach a large lecture section. How can I incorporate active learning?

Smaller classes are ideal for active learning, but it’s possible in larger sections, too. In the video below, Harvard physics professor Eric Mazur incorporates an active learning technique into his large class:

Though Mazur has about 80 students in this section, his class is still extremely active. By asking a challenging question, Mazur is able to build in substantial breaks for students to process, to teach each other, to problem solve, to change their mind, to come to the wrong conclusion, and to ask him questions. Professors of larger classes might be particularly interested in the active note-taking and the peer instruction portions of this blog.

I tried an active learning technique, and it was terrible! Students hated it / it was chaotic / students didn’t stay on task / students didn’t participate. What can I do to prevent this from happening?

While it’s gaining some popularity, active learning is still pretty new in the university setting. Students generally expect to be lectured, and when that doesn’t happen, it can be unsettling.

This is why it’s really important to consider how you’ll prepare your students for a more active classroom before simply plunging them into the activity.

Check out this blog post on common mistakes that instructors make in the active learning classroom which also includes some tips on how to deal with them.

Am I going to have enough time to plan out active learning activities?

Initial preparation time will increase, but activities can be used often. Some activities require little to no prep time. If time is a concern, use simpler activities (Faust & Paulson, 1998). Also, don’t feel like you need to change everything at once.

Similarly with group work, initial planning may be time consuming, but this will become easier over time (Cooper, 1995). Becoming familiar with new techniques is going to be challenging, but we encourage you to start small and continue to make progress.

Active learning slows down my class. How can I make sure to still cover everything?

Because students are more closely and carefully engaging with the material in an active classroom, they’re more likely to notice what they don’t understand and to ask questions Those questions take time. Things can get delayed.

However, it’s important to understand that “covering” material and student learning are not necessarily the same thing. Just because you introduced a concept doesn’t mean that a student has understood it. Students may not even understand that they haven’t understood something.

Here are a couple of suggestions for coping with the coverage issue.

Find out what is (and what isn’t) critical to teach.

Consider the “test-teach-test” method, which is commonly applied in language classrooms for finding out what students already know. The basic structure is this:

- Give students a short “test” to see what they already know. They’ll work on it alone, and then check it with a partner while you monitor and listen to who’s getting the right answer and who is still struggling.

- If you notice that one group is struggling and a group of students got the right answer, ask the correct group to explain it to the struggling group while you continue to monitor.

- Rather than covering EVERYTHING in the “teach” portion, you can now teach in the gaps of students’ knowledge. When students worked in pairs in the previous “test,” some of the teaching already happened. All you need to cover at this point is what’s still unclear. Sometimes, you can have a student who got the right answer show the class how they did it while pausing to emphasize relevant steps.

- Test students again. Did they get it this time? Can the group who struggled in the first “test” teach the group who got it while they give feedback?Test-Teach-Test gives students a chance to become aware of what they already know (and to communicate this to you). Test-Teach-Test also ensures that the “teach” section of the lesson is focused on critical topics and problems brought up by students (Cooper, 1995). The less critical topics can be excluded from the course entirely, assigned as outside readings, or briefly discussed (Yoshinobu & Jones, 2012).

Flip your classroom.

In a “flipped” classroom, students gain some exposure to course content by doing work outside of class time. This exposure does not need to be through a lecture delivered by you. In this video, Lindsay Masland, a psychology instructor at Appalachian State University explains how she provides multiple ways for students to learn the target information by giving them a curated “menu” of resources and a list of questions that they should be able to answer by the time they arrive to class. This allows students to select from materials that suit their learning. Then, instead of using class time as the first place where students can encounter an explanation of new concepts, class time is used to solidify understanding through the use of activities.

Will employing active learning mean that I have to spend more time grading low-stakes work?

Not necessarily! While active learning can generate more low-stakes work for you to grade, this is not always the case.

Consider incorporating jigsaw activities, like the ones modeled in this video, where students work collaboratively in small groups to teach each other what they know. Activities like think-pair-share (video) don’t generate any extra assessments to grade, but they let you check in one-on-one with student pairs as they discuss a question which can give you a better sense of what kinds of questions you need to raise with the entire group. You can use a class clicker system like Plickers or Top Hat to quickly check students’ individual understanding of a concept without needing to grade anything.

References

Braun, B., Bremser, P., Duval, A. M., Lockwood, E., & White, D. (2017). What Does Active Learning Mean For Mathematicians? Notices of the AMS, 64.

Cooper, M. M. (1995). Cooperative learning: An approach for large enrollment courses. J. Chem. Educ, 72(2), 162.

Faust, J. L., & Paulson, D. R. (1998). Active learning in the college classroom. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, 9(2), 3-24.

Hayward, C. N., Kogan, M., & Laursen, S. L. (2016). Facilitating instructor adoption of inquiry-based learning in college mathematics. International Journal of Research in Undergraduate Mathematics Education, 2(1), 59-82.

Yoshinobu, S., & Jones, M. G. (2012). The coverage issue. Primus, 22(4), 303-316.