This rather forbidding industrial complex near 38th St. and Berrian Blvd. in Astoria, Queens, was the site of several Chinese-run farms between the 1880s and about 1915.

The farms thrived as the Chinese community of New York grew. During the 1870s and 1880s, many Chinese on the West Coast left that region of the country because of the anti-Chinese violence they routinely encountered in small towns and large cities alike. Hundreds of these Chinese settled in New York City, which also became a major destination for the thousands of Chinese immigrants who entered the US in the 1890s and afterwards (often in violation of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act).

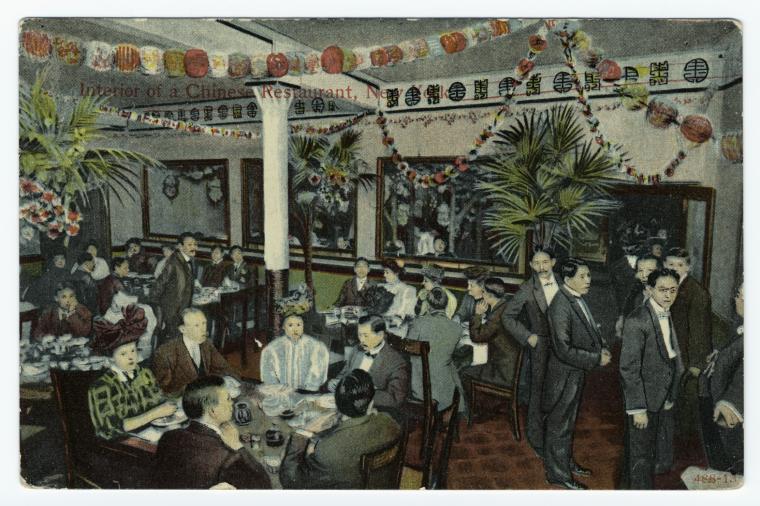

At this time, and for decades afterwards, most of New York’s heavily male Chinese population worked in laundries and restaurants. Chinese-run eateries in New York served very familiar versions of “Chinese” food, particularly the “chop suey” to which Americans had become addicted, as a Chinese newspaper of the time joked. But Chinese living in New York craved real Chinese food and the fresh vegetables needed to cook it, and a handful of entrepreneurial Chinese immigrants saw opportunity in this widespread desire for a taste of home. In 1883, the New York Times reported that Lum Thik Lup, Wah Lee, and other Chinese men had started farms in the Steinway/Astoria section of Queens in order to satisfy the community demand for Chinese vegetables.

Some workers lived on the rented plots–the 1900 census showed twelve Chinese settled on four adjacent farms off Bowery Bay Road (which no longer exists)–while others commuted to their farm jobs on the ferry that connected the nearby North Beach Amusement Park to Manhattan’s 92nd Street ferry pier. But the 1909 completion of the Queensboro Bridge and the 1917 inauguration of elevated train service to northern Astoria doomed the Chinese farms. The landowners in the area quickly developed their tracts for housing, forcing Chinese tenants to either give up farming or move closer to the city’s northern and eastern edges. Some trickled out to Flushing and to parts of the Bronx, but urban development eventually forced them out of business altogether.

The New York metro area’s Chinese American community grew quickly after World War Two, in large part because “warbride” legislation allowed China-born wives to join their husbands in America. Taking advantage of the renewed demand for Chinese vegetables, a number of Chinese Americans established new farms in New Jersey and Long Island. The most well known, Sang Lee Farms, remains in business today. But with Chinese produce readily available from Asia, Sang Lee now focuses largely on selling its produce at local farmers’ markets.

Sources for this post include the U.S. Census, the New York Times, the New York Public Library digital gallery, and the New York Municipal Archives.