On June 21, 2024, Yunjian (云间), author of novel Application for Divorce (离婚申请), was quietly detained in the night. Her suspected crime: writing danmei, a popular Chinese-specific genre of queer male romance and erotica that developed alongside its more popular Japanese counterpart, shounen ai (lit. “boys love”). In official terms, she was suspected “of producing and selling obscene materials for profit.”

Since last June, authors have been silently disappeared off Taiwanese-based website Haitang Literature City. Late December, they revealed that they had been implicated by a series of police crackdowns in Anhui province, east China, specifically targeting danmei authors.

It’s not merely a matter of sexual impropriety. Amidst the turbulence of beloved authors being arrested, a frightful note on censorship law incited online outrage: sexual assailants get off easier than erotica authors. More specifically, authors earning over 250,000 yuan (USD 34,700) from “obscene materials” can face a lifetime of imprisonment—though the severity of the sentence could, hypothetically, be lessened by paying back “between one and five times the amount of illegal income.” Authors who made less were typically placed on probation. Meanwhile, the punishment for rape of a female minor by guardians under “heinous circumstances” is between three and ten years.

For Yunjian, it wasn’t until December 6th that she received her official verdict: a sentence of 4 years and 6 months, with a fine double her earnings.

According to South China Morning Post, as of January 1st, Anhui police had detained over 50 writers in China since June 2024.

Taiwan, the birthplace of beloved Brokeback Mountain director Ang Lee and the origin of queer film Your Name Engraved Herein is a known safe haven for sexual minorities and free speech. Haitang Literature City previously served that purpose for authors of queer fiction, but authors are frequently finding themselves with nowhere for their craft to go.

Domestic censorships had grown tighter. Since previous years, the fate of progressing live action adaptions for danmei novels have been left in the dark. Since 2021 and 2022 respectively, Immortality, based off beloved novel The Husky and His White Cat Shizun (dubbed 2HA, as a shortening of its original Chinese name), and Eternal Faith, the live action for Heaven’s Official Blessing (dubbed TGCF), were under rigorous censorship review before news of releases ambiguously fizzled out.

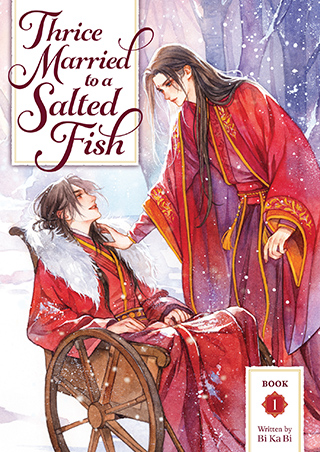

However, Heaven’s Official Blessing also has a widely accessible Netflix-housed donghua animation adaptation, and both 2HA and TGCF have official translations licensed by a Los Angeles publisher, Seven Seas Entertainment. Previous works of Mo Xiang Tong Xue, author of TGCF, have also spurned other adaptations: including a live action Chinese drama The Untamed, the Mo Dao Zu Shi donghua, and recently, even a four-part stage play in Japan. Seven Seas’ latest acquisition, Thrice Married to Salted Fish, was just announced last week. Suffice to say, danmei isn’t a genre kept in the dark, or to be shelved in with the “pornographic” label. It is a thriving worldwide phenomenon.

Due to the covert nature of queer fiction in China, even Mo Xiang Tong Xue, was at one point suspected of being arrested, with rumors claiming either censorship or tax evasion.

The Haitang incident is a fearmongering response to the increasing popularity of danmei. “They were all arrested on the same day, and the police had all the authors’ information; it was clear that they had been targeted,” speculated Chenchen, a longtime danmei reader.

As a result of the fines, many authors still had to turn back to writing to pay off their dues.

The question of free speech is complex—the legislation is largely freely interpreted by those in power. What constitutes as “obscene materials,” and how do we measure the “social harm” that dictates the severity of a sentencing? The lines keep shifting: whereas euphemisms used to slip under the radar, new reinterpretations of censorship easily place restrictions on “nothing below the neck.”

In one interview by RFA Mandarin, longtime writer Si Yueshu laments that the lines keep shifting for authors, despite danmei being a low-paying labor of love. “You can’t actually know what you’re allowed to write and what you’re not allowed to write,” she says. “Very successful authors usually upload three chapters a day, or more than 10,000 words, and the most they can make is around 20,000 yuan (US$2,740) a month.”

The extensive fines for this hard-earned salary become, more clearly, examples of economic exploitation.

Danmei remains an explorative space for women and queer individuals to express their sexuality. Infringement of this freedom based on historical stigma against homosexuality has long been criticized as outdated. Why must independent queer authors be martyrs for creative expression? And for the average American fan, what can they do besides consumption?

For some like Yunjian, who have been facing poverty, medical conditions, and innumerable other hardships, donations have helped authors stay afloat.

In the Western or even Chinese diasporae consciousness, danmei isn’t without its faults, in terms of reinforcing certain gendered stereotypes or beauty standards. Yet that critique is entirely quashed under the face of legislative censorship, which seeks to perpetuate the idea that gay people, below the neck, have never existed in China at all.

Which is, historically, challenging to prove.