I can’t say that I was absolutely thrilled when I learned of my most recent assignment. Nonetheless, as one of the few ambassadors of Bristonia responsible for developing diplomatic relations, I must take each facet of my job very seriously. My name’s Colin Starks, and I’m a servant to the people of the timeless republic that is Bristonia. My role entitles me to meet with various leaders around the world to negotiate everything from trade agreements to peace treaties, and I was made to understand that this next mission was of paramount importance. A positive relationship with OGS was crucial to our Bristonia enjoying her economic prosperity; I learned of this straight from the horse’s mouth during my briefing with our prime minister. My being sent to meet with some of the leaders of the nation was to be interpreted as a gesture of good faith, one of those publicity stunts so crucial to the game of politics. In the process, I was also expected to learn a few things about the political and economic structure of the republic, as of these things we knew very little. Yes, OGS has been very secretive and secluded throughout the decades. The only thing we’re absolutely sure of is their ability to manufacture products of excellent quality. The OGS standard is synonymous with the finest attention to detail and uncompromising durability, and the most well-off Bristonians are willing to pay small fortunes for the social status that comes with owning a piece of OGS craftsmanship. There are rumors that all citizens of OGS lead a life of extreme luxury due to both the exceptional nature of their goods and the economic prosperity they enjoy as a result of the high demand of their exports.

I speak of rumors because our lack of knowledge about OGS forces some rumors to morph over time into widely accepted fact. We have never had a diplomatic mission with the country in the past, and OGS is always conspicuously absent from all the various nationwide assemblies held throughout the year. Yet here I am speeding across vast, empty valleys below in a private jet, flying in the direction of the unknown with ice clinking quietly in the glass clutched by my right hand. My colleagues warned me to stay diligent during my visit with OGS; they explained some of the unapologetically unnerving stories about the society that were well known among Bristonians. My wife also had a few cautionary words for me, mostly that although OGS was also an English-speaking country, the people undoubtedly led different lives than what we would consider to be normal and traditional. It’s true that life in capitalist Bristonia hasn’t changed much over our country’s long history, which is more than can be said for the relatively new state of OGS and their recent wars and volatile independences. I admit all of these discussions did have an effect on me, but a swig from my glass did more than enough to calm my nerves.

Upon landing I was greeted by a representative of OGS’s minister of economy and taken to meet with the minister himself. Walking through the elegant airport, I was surprised to see that it was somehow deserted during this normally busy hour, as the aid and I were the only souls within sight. I was brought towards a black car, out of which stepped a tall, well-dressed man with a dark skin complexion and a smile that seemed to reach from ear to ear. I approached him and held out my hand to meet his.

“Mr. Starks, allow me to be the first to formally welcome you to Our Great Society! We have nothing but deep admiration for you Bristonians, and are very pleased that we may host you so you may observe our country and understand what we are so proud of. I am Donald DeFaro; I’m honored with the title of minister of economy. Please, come inside the car with me, so we may discuss today’s plan of events.” He spoke with an interesting accent, and a voice that threw itself far and wide; it was the voice of a leader. I followed his instruction and sat down in the comfortable and pleasantly decorated convoy.

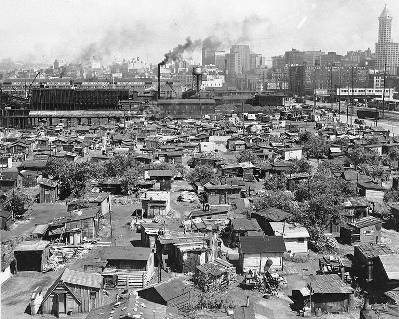

“Pleased to make your acquaintance, Mr. DeFaro. I must say I’m looking forward to learning everything I can about your fine nation with a very eager interest. OGS enjoys an amicable reputation amongst citizens in Bristonia. There is, however, still a certain aura of mystery surrounding your country, and people have taken it upon themselves to construe fantastic fairy tales about what goes on within your borders.” As I peered through the window to take in my first views of the streets of OGS, I realized just how naïve all these tall-tales really were. The city I was brought to examine had no streets of sparkling gold. Rather, what I saw outside was a very well organized industrial hub. All around me where the smoky outlines of large factory complexes, with steam billowing out of a plethora of chimneys and shadows of quick movements just visible through foggy windows, and tall, brick towers with grids of hundreds of windows along their walls, framing what I assumed were tiny apartment spaces.

“As you can see by the various manufacturing facilities around us, Mr. Starks, our nation is built around the hard-working spirit of the people of OGS. Here, everybody is a part of the modern proletariat, and everybody must work. These are the principles that have given us success and a healthy economy. You will notice this when we visit one of our factory centers, where we produce some of the goods that are so sought after all around the world. After this, we will travel to the seat of government, housed in a different district, where a feast shall be ready for us. There you shall meet and parlay with some of my colleagues: the leaders of OGS.”

I could see that the minister meticulously organized this schedule as to impress me, so I may bring back good word of OGS to my superiors. The mention of a grand feast and a socializing hour were no different. I wasn’t going to let myself be swayed easily, however. I already had some prying questions about what I was seeing. Just as I had noticed a lack of people at the airport, looking out onto the streets I saw no pedestrians on the sidewalk, no cars on the roads. I raised this point to my guide.

“Ah yes, there is a simple explanation to this. You see the clock just struck 1600 hours, and all across OGS the hours between 800 and 1800 are designated for work. You have seen no people on the streets nor in the airports because every citizen is presently busy with his or her assigned role in one of these numerous manufacturing centers you see outside. After work hours conclude, everybody is free to enjoy any diversions they wish in their own respective districts. We are currently in District Adrenaline, so named because of the citizens…” Defaro suddenly hesitated. “… fondness… of activities that get their blood rushing.”

I thought this was a strange comment, and a strange name for a neighborhood, but nonetheless I smiled and nodded in the minister’s direction. We soon arrived at our destination, and I was brought on a tour of a manufacturing facility that was responsible for the production of luxurious home furniture. The sheer level of commotion, of movement and of hustle and bustle inside, was overwhelming at first. However, the more I observed the workers by the production line, those preparing raw material, and those boxing up finished products, the more I realized that this was an organized chaos. The amount of time each group of workers spent on a single piece of furniture was unnerving. I could plainly see how each product is indeed manufactured to the highest detail and quality. The goods exported by this nation deserved their upscale reputation. However, I didn’t understand how they could afford the time to be so meticulous in their manufacturing process, and still maintain a steady level of production. Certainly, this must require a huge number of employees to be working around the clock at this factory. I remembered what I saw outside the window on the drive over here; there were factory buildings as far as I could see. How large did OGS’s population have to be to allow for this?

All of my questions went unanswered as minister Defaro pushed me into the employee cafeteria, claiming that having an end-of-work-day dinner here would make my experience more authentic, and yelling that he would return promptly to resume our planned schedule. Before I even could think of protesting, he was gone, and I was left alone in this enormous mess hall. All around me, workers were sitting down at their tables in front of plates where meat, potatoes, and vegetables were piled massively high. As I was admittedly feeling hungry at this time, I stood in line to receive my serving. When I helped myself to what I believed was a healthy portion of some kind of mystery meat I could not identify, I noticed several people glaring at me inquisitively as they piled their plates high with absurd amounts of food. I would have to ask the minister as to whether he was aware of people following such extreme diets.

Suddenly, I could hear a bell ringing loudly, and all the people around me started to get up and walk towards a single direction. Men approached me, shouting, “Come on then, work is over. You know how all this works! Let’s go, up you go, time to leave, come then.” I was being lifted off my seat, forcefully pushed towards a set of doors. I tried to explain myself and tell them who I am, but the horror of the whole situation caused my words to get caught in my throat. Through these doors lay the darkness of the nighttime, the uncertainty of the street, and the mystery of OGS.

Once I was outside, I was finally able to see people walking along the sidewalks, but I was alone without my guide. The doors to the building I had left were locked shut behind me and I couldn’t find the car that had brought me here. I decided it was best if I stay close to this area, as somebody simply will have to come get me from here eventually. Part of me longed for the safety of the minister’s company and the comfort of the feast, but at the same time I knew this was my opportunity to see what happens here after work hours have concluded. There was much activity happening around: some people milling about the sidewalks, some coming in and out of the brick apartment complexes, some driving cars. I noticed the cars were being driven at speeds that no Bristonian would have dared attempt lest he be penalized with a costly speeding ticket. OGS must have a more relaxed stance on road speed limits in major cities, I reasoned. As a man whose job is to visit different countries and investigate their cultures, I often found myself drawn to observing such little differences in organization. I started to wander aimlessly to look for more of such discrepancies so I can have much to talk about when I return to Bristonia and am inevitably met with prying questions from my colleagues.

However, my attention was constantly drawn back to the automobiles on the street. They were moving at speeds well beyond any I’ve ever seen, or any reasonable human being would be comfortable with. The drivers were slicing through traffic, driving the wrong way, and hugging the curves tightly as if emulating scenes from an action-driven B-movie. All around me I heard the screeching of tires against asphalt, the rumble of engines being pushed to their limits, and the shriek of metal scraping against metal, which was apparently coming from accidents happening on adjacent streets. I stopped dead in my tracks to try to take this all in, and just then a four door sedan plowed head on into the wall right in front of me at a spectacular speed, the momentum of which catapulted the driver through his windshield. His body slid off the wall and lay in a crumpled heap in front of me, the eyes lifeless and bloodied.

At this moment I turned and ran as fast as my legs would take me in the opposite direction. I had already lost my sense of direction and the building that I had originally intended on staying close to, but I could not stay in one place with this madness happening around me. Turning the next corner, I found a band of motorcyclists plowing towards me on the sidewalk at an absurd speed. I clung to the wall as they passed me, performing perilous wheelies and handstands. One of these riders lost his balance and skidded on the ground while simultaneously being crushed by his bike. He was not wearing a helmet nor any protective gear, which should have been an obvious necessity considering the danger of his stunt. The injuries he sustained were surely fatal. I could not bring myself to look on much longer and kept running along.

I was witnessing the same events on every street that I ran past. There was a total disregard for safety and moderate, rational thought. All citizens were exposing themselves to extreme danger, and it seemed nobody around was sane enough to realize the hazard behind their actions. It was as if there had been a complete suspension of rational regard for one’s health in the pursuit of daredevilry.

My leg muscles were sending distress signals to my brain, begging me to stop my running when I noticed DeFaro’s car pulling up beside me. The door closest to me opened; I didn’t need to be told to get in. The minister was sitting inside, and I lay panting next to him. “Do you have an explanation for the hell that is going on out there? In your own illustrious nation?” I demanded of him.

Defaro sat looking pensively outside the window. I could tell he was frustrated by the restrained tone of his voice that was so booming earlier and the fact that he didn’t look at me when he spoke. “You weren’t supposed to see this. Why did you leave the factory, Mr. Starks?”

“Were you intending on showing all of this to me, or was I supposed to conveniently leave this anarchy out of my report to the president?”

“Oh, no, this is no anarchy. Believe me, this is all permissible by the Constitution of Our Great Society. Actually, it’s something that’s required of all citizens. What you saw was the good people of District Adrenaline willingly participating in their own government mandated acts of extremity. Everybody here loves their intense lifestyles and is very happily accustomed to the extreme actions they must take as citizens of District Adrenaline, Knowledge, Sin, or Sadism. And we public servants, residing in District Authority, forfeit our right to such a glorious way of life so we may govern our people.”

We came to a stop. Defaro silently left the car and entered into a building similar to that of the factory complex I had visited before. I was sure that this wasn’t the feast I was promised, but I had no choice to follow him inside.

“But what about the lives of your people?” I asked, as I struggled to keep up with his pace through the inside of the building. He was leading me through several series of doors, but it was too dark to see what lay around me. “I saw countless amounts of meaningless deaths while I was out there. How can you govern people if you aren’t interested in their well-being?”

“Every citizen is a vital cog in the well oiled machine that is Our Great Society. And what is a cog but a simple device with a function, and another cog pushing it to aid in that function’s execution? In our society, a citizen serves his country by working in a manufacturing plant, directly contributing to the health of our economy. But the quality of the excellent goods we produce requires several hours of work in an unrewarding environment. So the trick is to manipulate this cog, to make it love its function without noticing the pain of its execution. Thus, to keep our citizens’ minds from splitting under the weight of the physical and mental duress of factory life, we give them their pursuit of extremism to busy themselves with. They are content at work, as they are looking forward to satisfying their constant hunger for thrill-seeking, for hedonism, for knowledge…”

“But this is monstrous!” I protested, uncomfortably aware of the increasing hostility of our conversation, but nonetheless determined to speak against the treachery I am hearing. “How can you pretend to serve the interests of your people when you are the very ones who are forcefully deciding those interests for them? You have no respect for them and their rights as human beings!”

“Mr. Starks, I understand that at this point you know well more about the rules of our nation than we have intended on sharing with you. You of course understand that we do have a reputation to uphold with the countries that we trade with, including your own fine nation. Thus we will have to resolve this issue somehow, but for now, know this: each one of our tens of millions of citizens—“

“Tens of millions?” I had to interrupt him here, as this far surpassed any estimate Bristonia held of the population of OGS.

“Yes, indeed, tens of millions. How else would our production level be so great while maintaining the high quality of our products? We owe this population to a miracle of modern technology, and allow me to present to you now another scientific innovation that allows our society to thrive. As I was saying before, each one of our tens of millions of citizens is of the upmost utility to the rest of society as a whole, in life…” He paused; suddenly his ear-to-ear smile crept over his lips. It was the smile of a malevolent despot. “… and in death.”

The room around us was thrust into light. My eyes struggled to adjust to the sudden brightness, but when they finally did, I would have preferred to stay blind forever than witness the sight I was about to behold. We were in a production facility with conveyer belts, containers, and furnaces not unlike the furniture mill I had visited before. But in this room, the raw material was no longer wood and iron. It was the corpses of men and women, stripped of their clothing and cut up into pieces. They were being fed into some grisly machine in which human remains entered on one side and bright red raw hunks of meat emerged on the other. My brain initially refused to process what my eyes were seeing, but soon I cracked and fell over onto the floor as I heard the monster continue to speak.

“I trust you enjoyed your meal at the factory cafeteria earlier today? You Bristonians are said to fatten your game up before you send it to the chopping block, but we’ve found that years of hard labor are what really make the meat most tender and delicious!”

I understood all of this. An involuntary gag reflex took over my whole body and shook me to my core as I purged out every evil thing I had taken into my body in my time in this horrendous nation of cannibals. I began to crawl away from the man who seemed to enjoy my suffering, and used a nearby ledge to hoist myself up. I was in a daze, in no state to make any substantial movements, but I knew I needed to formulate some kind of escape plan. I leaned over this ledge to regain my balance, and realized it was overlooking a deep precipice. I could just make out shadows of heads, feet, arms, and other organic components of the human body that were thrown together haphazardly into a pile below. Then I felt a soft push behind me, gentle, almost guiding me over the edge. I fell forward, fall toward the darkness, fell forever.

The year is 2017, and, as we would expect, the streets of Los Angeles are crowded with masses of people. However, in this era, rickety, crude spacecrafts, tremendous, towering black obelisk buildings, and animated billboards hundreds of stories tall add to the already chaotic setting. The city is under a constant state of torrential downpour and fog, with a seemingly endless amount of dirty neon signs peering through the gloomy musk. Muted colors, constant smokiness, and a score of synthesizers and futuristic sound effects all inspire the film’s finely executed gritty urban dystopia setting.

The year is 2017, and, as we would expect, the streets of Los Angeles are crowded with masses of people. However, in this era, rickety, crude spacecrafts, tremendous, towering black obelisk buildings, and animated billboards hundreds of stories tall add to the already chaotic setting. The city is under a constant state of torrential downpour and fog, with a seemingly endless amount of dirty neon signs peering through the gloomy musk. Muted colors, constant smokiness, and a score of synthesizers and futuristic sound effects all inspire the film’s finely executed gritty urban dystopia setting.