After watching Gilda and Laura in one night, I began to ponder how one watches one without the other. Due to the class assignment, I had the pleasure of watching them back to back and therefore was able to compare and contrast two spectrums of film noir. This comparison led me to an understanding that Laura Mulvey might frown upon – if used correctly, female sexuality in the film noir era can actually empower the woman. True, female sexuality would have been inserted into the films of this age by the hands of the men in charge. Admittedly, it probably wasn’t intended to empower the female characters involved. Nonetheless, a sexual female role is not necessarily a passive one.

According to Mulvey, “traditionally, the woman displayed has functioned on two levels: as erotic objects for characters within the screen story, and as erotic object for the spectator within the auditorium, with a shifting tension between the looks on either side of the screen.” (p. 488) But Gilda begs to differ, Mulvey! Yes, Gilda is erotic. Yes, Gilda might serve as the erotic object for characters within the screen story. However, she is more than the objectification of female beauty. To truly appreciate this fact we need to compare her to a character that fits Mulvey’s definition perfectly. Conveniently, we watched Laura.

Laura is a girl in need of a good saving. In fact, she was saved several times in the movie. First, Waldo saves her from a boring and pointless career. Then, Shelby saves her from Waldo. Finally, detective McPherson saves her from death by Waldo, love with unfaithful Shelby, and probably everything else one can imagine as bad and dangerous. Essentially, we could replace Laura with a cardboard box and the movie would lose very little besides something nice to look at. Of course, I exaggerate but the main point is that the plot does not depend on Laura. She doesn’t move the sequence of events – the men do. Laura’s arguably main addition to the storyline is her traveling to the country for the weekend of the murder. However, it isn’t Laura’s trip to the country that moved Waldo to murder. She could have gone to the country, New Jersey, Paris, or Jupiter; it wouldn’t have mattered to the storyline because Waldo killed Shelby’s lover for his own reasons. Thus, in terms of Laura, Mulvey is right – she does stand “in patriarchal culture as signifier for the male other, bound by a symbolic order in which man can live out his fantasies and obsessions through linguistic command” (p. 484)

Gilda, unlike Laura, is not a passive female character. Rather, she makes her own fate and asserts her own downfall. Gilda chooses to marry Ballin, to make Johnny jealous, to run away, to come back, etc… Her decisions didn’t just matter to the plot, they made the plot. These important decisions relied heavily on sexuality, which is why Mulvey would be unhappy with this film. However, though Gilda depended on her sexuality, she didn’t weaken her own free will by doing so. She used what tools were available to her at the time to get what she ultimately wanted – Johnny. Surrounded by strong male characters and an almost entirely male gambling society, Gilda utilized her beauty and seductiveness for her own advantage. How else would she have gotten Johnny? She couldn’t make him notice her by becoming his casino boss, by making more money than him, or by rising to a higher social stature than him on her own. All she could do was be sexier than him and marry “well.” Though her decisions did backfire at her by making Johnny more angry than jealous, at the end she ended up with her man. Without Gilda the character, there would be no Gilda the movie. Thus, though Mulvey is correct to assert female characters serve as pleasant objects for men to look at in film noir films, Gilda’s character also managed to create her own destiny and therefore stands as an example of film noir’s strong, active, AND beautiful female personality.

The following is a clip I found comparing Gilda and Laura. In this short clip, one can pick up on the differences between the characters and contrast their strength and assertiveness. Though both characters are beautiful in the scenes, their beauty comes to serve different purposes and is more intentionally used by Gilda than by Laura. Enjoy the background Coldplay.

In Martin Scorcese’s 2006 crime film The Departed we are introduced to William Costigan, played by Leonardo DiCaprio, who is an undercover cop working for Frank Costello the Irish Mob boss from Boston, played by Jack Nicholson. Then we also have Colin Sullivan, played by Matt Damon, who acts as Costello’s inside man in the police department. Throughout the film each of these characters elicit fear, anxiety and paranoia. The character that most strongly feels these emotions is DiCaprio’s William Costigan. Costigan is introduced to the dark, demented world that is the Irish mob. Every day he fears for his life, thinking any minute it could be his last. His anxiety and paranoia strengthens so much so he begins going to therapy and taking prescription drugs. He feels that either Costello is going to find him out or that his own police force is going to give up on him and allow him to rot in the depth of the criminal underworld.

In Martin Scorcese’s 2006 crime film The Departed we are introduced to William Costigan, played by Leonardo DiCaprio, who is an undercover cop working for Frank Costello the Irish Mob boss from Boston, played by Jack Nicholson. Then we also have Colin Sullivan, played by Matt Damon, who acts as Costello’s inside man in the police department. Throughout the film each of these characters elicit fear, anxiety and paranoia. The character that most strongly feels these emotions is DiCaprio’s William Costigan. Costigan is introduced to the dark, demented world that is the Irish mob. Every day he fears for his life, thinking any minute it could be his last. His anxiety and paranoia strengthens so much so he begins going to therapy and taking prescription drugs. He feels that either Costello is going to find him out or that his own police force is going to give up on him and allow him to rot in the depth of the criminal underworld.

Walter O’Neil of “The Strange Love of Martha Ivers” is one of the weakest male characters I have ever encountered. His anxiety is like a dark cloud hovering over the film. I feel anxious just watching Walter. In fact, Walter acts as a doormat for his father, Martha his wife, and his childhood friend Sam.

Walter O’Neil of “The Strange Love of Martha Ivers” is one of the weakest male characters I have ever encountered. His anxiety is like a dark cloud hovering over the film. I feel anxious just watching Walter. In fact, Walter acts as a doormat for his father, Martha his wife, and his childhood friend Sam.

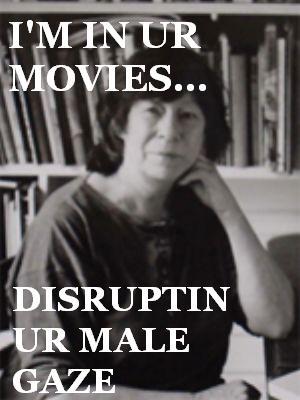

For Tuesday I’ve asked you to read British film theorist

For Tuesday I’ve asked you to read British film theorist