Photograph of a woman with a crown and scepter.

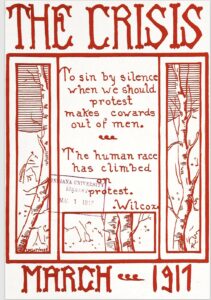

The Crisis started out as a publication with the intent of highlighting real African American culture. The many aesthetically pleasing covers we see not only created a national buzz, but they also emphasized identity.

“The Crisis in its layout and content stages a jointly political and aesthetic conflict. Columns of numbers arranged chronologically, building to the present, attest to the contemporary consolidation of a black print culture, one that can simultaneously distribute positive images of African Americans and take out negative ones.” (p.81, Harris, Printing the Color Line in The Crisis)

Prior to this publication, African Americans were painted in a way as viewed by white people. The Crisis combatted racial prejudice and sought to paint African Americans how they rightfully should be portrayed. It was important to ensure that these covers were seen as proper and pleasing to the eye. Not only to help prevent discrimination, but also to accentuate the magnificence of African Americans. Seeing covers of beautiful women, proper-looking men, athletes, educated people, etc. invokes a sense of amazement. It makes you wonder, how are these covers influencing the people and their identities?

The queen we see in the March 1913 cover oozes strength and excellence. She does the job of being appealing in a political way, but there’s also something else. She’s beautiful, she’s graceful…she’s an it-girl. For all the girls grabbing this cover, it must’ve made them proud. She appeals to readers because she influences thoughts like “I am a queen”, or “I am strong”, or even “I am a leader”. The cover creates self-confidence and the idea that I am worth it, and I too can be that girl. It’s a wonderful feeling to feel represented and portrayed in such a positive light.

As Harris suggests, “The Crisis becomes quite clear here: first, it wants to aggregate information on African American achievements and circulate them to a national reading public so as to provide a counterhistory to racist mass culture, but it also wants to project a future when such work will not be necessary—that is, like the eponymous character in Cather’s “Ardessa,” a future in which it will have worked itself out of a job.” ( p.69, Harris, Printing the Color Line in The Crisis)

The Crisis calls attention to the importance of identity. African Americans have, for so long, fought to receive dignity and human respect. These publications shed light on the idea that African Americans have an identity. And it’s just as strong as any other race. So, while the basis of The Crisis was to counter injustices, its long-term goal is more than that. It hopes to reach a point in time where there is no more need to defend the race. It hopes to reach peace and continue on printing publications that share who African Americans are and what makes them so special. It hopes to highlight pride and show the new generations how stunning and talented their ancestors before them were and how they too are just as extraordinary. It should also invoke a sense of drive to want to love and be the best version of yourself.

Imaginative work leaves ample room for the viewer to interpret the piece according to their own needs. Nonfiction work slashes the room for interpretation to an infinitely small percentage. Fictive work concerns the viewer with the appearance of what the creator intends. Nonfictive work concerns the viewer with the actuality of what the creator intends. Nonfictive work does not oppose ignorance whereas fictive does. Poems are open to interpretation and data is not.

Imaginative work leaves ample room for the viewer to interpret the piece according to their own needs. Nonfiction work slashes the room for interpretation to an infinitely small percentage. Fictive work concerns the viewer with the appearance of what the creator intends. Nonfictive work concerns the viewer with the actuality of what the creator intends. Nonfictive work does not oppose ignorance whereas fictive does. Poems are open to interpretation and data is not.