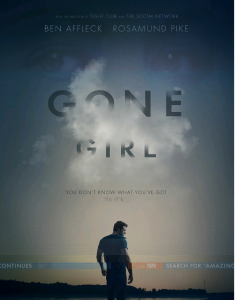

David Fincher’s Gone Girl has hit the cultural zeitgeist. It has been the subject of more think pieces and op-eds than perhaps any film this year. And although not really an “indie” film, the timeliness of the film’s subject matter and the national debate that it has caused makes it a good topic of conversation for this blog. Plus, I don’t think there is any credible cinephile out there who would argue that Fincher isn’t an auteur. And that is one of the things this blog does, it discusses the films of our greatest auteurs.

The main and most contentious debate surrounding Gone Girl is the film’s gender politics (warning: spoilers ahead if you haven’t seen the film). Based on the best-selling novel by Gillian Flynn, it tells the story of Amy and Nick Dunne, a perfect-looking couple from New York whose marriage goes sour after moving to Missouri. After learning his wife has disappeared and perhaps murdered on the morning of their fifth wedding anniversary, Nick becomes the prime suspect and the focus of an excruciating media witch hunt. But we then learn that Amy has in fact faked her own kidnapping and murder in order to punish Nick for his affair with a younger woman.

Throughout the film, Amy lays waste with any man that comes across her with false accusations of pregnancy, domestic abuse and rape.

So is Amy a feminist hero who is using her power as a woman to get back at the men who have emotionally neglected her? Or is she the embodiment of the worst kind of stereotype of psychotic women who make up allegations of rape and abuse and even commit murder?

I would argue that it’s neither. I especially disagree with the theory that the film is sexist. Amy does not do the things she does because she’s a woman; she does it because she’s a psychopath. Amy is not meant to be a literal representation of all women. The same way that other cinematic psychos like Norman Bates and Hannibal Lecter were not meant to be a representation of all men.

Maria Santic, a junior who minors in Women’s Studies at City College in New York agrees. “Why do all women on television and film have to be perfect saints? Women are extremely complex creatures,” she says. “I think Amy Dunne is the most three-dimensional female character I’ve seen in any film this year.”

Santic thinks that we do a disservice to female characters if they’re all portrayed as inherently good. “Amy wasn’t just in the kitchen being the supportive, devoted wife to the male protagonist; she was actually running the film’s narrative,” she says. “Nowadays you hardly ever see that on film.”

Santic points to an article in the New Republic by Becca Rothfeld in which she argues that Amy is a fascinating throwback to the femme fatale archetype of the Film Noir genre that was very popular in the 1940’s. Ironically, this is a decade in which female characters actually had more agency than they do in today’s films. In that article, Rothfeld compares Amy to the grandmother of all femme fatales, Phyllis Dietrichson of the 1944 classic, Double Indemnity.

I would also compare Amy to another intriguing archetype: the male anti-hero that we see on cable television today. Like Tony Soprano, Donald Draper and Walter White; Amy Dunne is a protagonist who does morally reprehensible things while also still maintaining the audience’s sympathy. The only difference is that Amy does it in high heels, and that shouldn’t be held against her.